In what follows I will take it for granted that, in adult humans,

there is a system of object indexes which enables them to track

potentially moving objects in ongoing actions such as visually tracking or

reaching for objects, and which influences how their attention is allocated

\citep{flombaum:2008_attentional}.

- guide ongoing action (e.g. visual tracking, reaching)

- influence how attention is allocated

- can conflict with beliefs and knowledge states

This system of object indexes

does not involve belief or knowledge

and may assign indexes to objects in ways that are inconsistent with

a subject’s beliefs about the identities of objects

\citep[e.g.][]{Mitroff:2004pc, mitroff:2007_space}

- have behavioural and neural markers

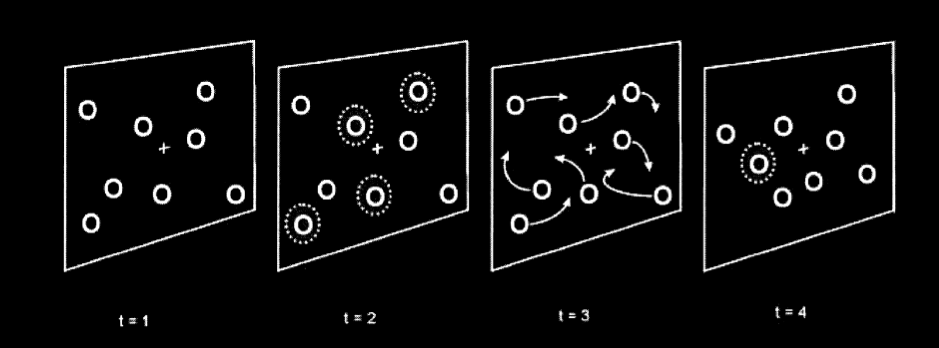

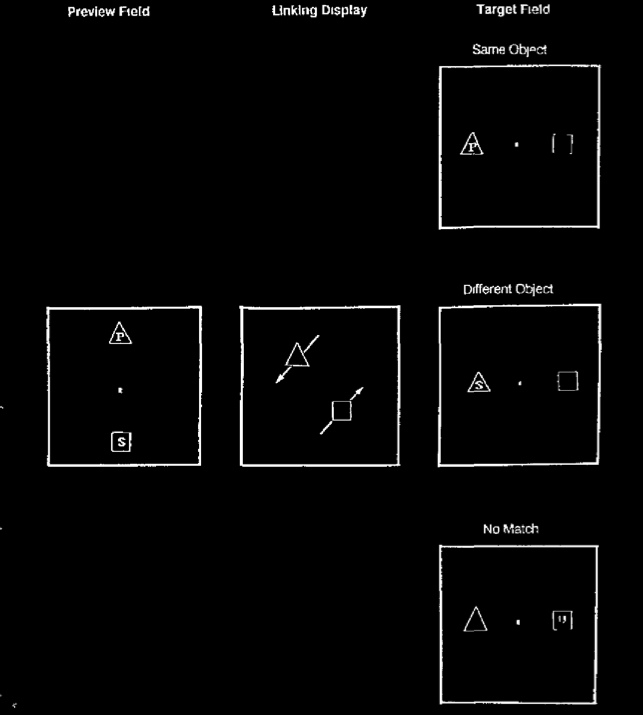

We have observed one behavioural marker of object

indexes, namely the object-specific preview benefit.

There are also neural markers of object indexes.

That is, in adults there is a pattern of brain activity which appears to be

characteristic of processes involved in maintaining an object index

for an object that is briefly hidden from view.

- are subject to signature limits

The system of object indexes is also subject to signature limits.

In general, a \emph{signature limit of a system} is a pattern of behaviour the system exhibits which is both defective given what the system is for and peculiar to that system.

One signature limit of a system of object indexes is that featural information sometimes fails to influence how objects are assigned in ways that seem quite dramatic.

Let me illustrate ...

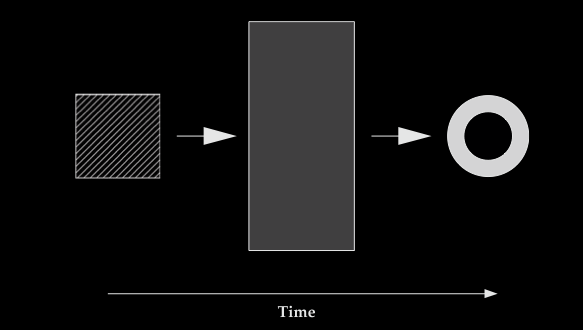

In this scenario,

a patterned square disappears behind the barrier; later a plain black ring emerges.

If you consider speed and direction only, these movements are consistent with there being just one object.

But given the distinct shapes and textures of these things, it seems all but certain that there must be two objects.

Yet in many cases these two objects will be assigned the same object index \citep{flombaum:2006_temporal,mitroff:2007_space}.

So one signature limit of systems of object indexes is that information about speed and distance can override information about shape and texture.

- sometimes survive occlusion

As the findings I just describes imply,

object indexes can survive brief occlusion.

That is, an object index

can remain attached to an object even if that

object is briefly occluded by a screen.

(Sameness of object index may be detected by the presence of an

object-specific preview benefit).

To clarify terminology,

I should say that whereas I’m talking about object indexes,

researchers more typically interpret this research in terms of object

files.

I’m sticking to object indexes rather than object files for

reasons of simplicity and caution.

If you believe in object files then you can interpret what I’m saying

as referring to object files.

And if you have doubts about object files, you might still have reason

to accept that a system of object indexes exists.

So far I have been talking about object indexes in adult humans.

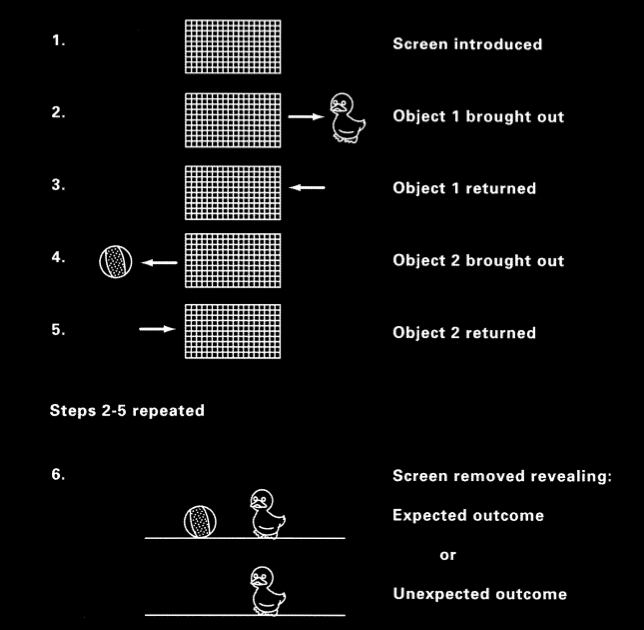

But our interest in object indexes stems from a hypothesis about

four-month-old infants’

abilities to track briefly occluded objects.

According to this hypothesis, these abilities depend on a system of

object indexes like that which underpins multiple object tracking or

object-specific preview benefits

\citep{Leslie:1998zk,Scholl:1999mi,Carey:2001ue,scholl:2007_objecta}.

What makes this hypothesis attractive?

One reason the hypothesis seems like a good bet is that object

indexes are the kind of thing which could in principle explain

infants’ abilities to track unperceived objects because object indexes

can, within limits, survive occlusion.

If we consider six-month-olds, we can also find behavioural markers

of object indexes in infants \citep{richardson:2004_multimodal} ...

... and there are is also a report of neural markers too \citep{kaufman:2005_oscillatory}.

(\citet{kaufman:2005_oscillatory} measured brain activity in

six-month-olds infants as they observed a display typical of an object

disappearing behind a barrier.

They found the pattern of brain activity characteristic of maintaining

an object index.

This suggests that in infants, as in adults, object indexes can attach

to objects that are briefly unperceived.)

The evidence we have so far gets us as far as saying, in effect, that someone capable of committing a murder was in the right place at the right time.

Can we go beyond such circumstantial evidence?

The key to doing this is to exploit signature limits.

\citet{carey:2009_origin} argues that what I am calling the signature

limits of object indexes in adults are related to signature limits on

infants’ abilities to track briefly occluded objects.

To illustrate, a moment ago I mentioned that one signature limit of

object indexes is that featural information sometimes fails to influence how objects are assigned in ways that seem quite dramatic.

There is evidence that, similarly, even 10-month-olds will sometimes

ignore featural information in tracking occluded objects

\citep{xu:1996_infants}.%

\footnote{

This argument is complicated by evidence that infants around 10 months of age do not always fail to use featural information appropriately in representing objects as persisting \citep{wilcox:2002_infants}.

In fact \citet{mccurry:2009_beyond} report evidence that even five-month-olds can make use of featural information in representing objects as persisting \citep[see also][]{wilcox:1999_object}.

%they use a fringe and a reaching paradigm. NB the reaching is a problem for the simple interpretation of looking vs reaching!

Likewise, object indexes are not always updated in ways that amount to ignoring featural information \citep{hollingworth:2009_object,moore:2010_features}.

It remains to be seen whether there is really an exact match between the signature limit on object indexes and the signature limit on four-month-olds’ abilities to represent objects as persisting.

The hypothesis under consideration---that infants’ abilities

to track briefly occluded objects depend on a system of

object indexes like that which underpins multiple object tracking or

object-specific preview benefits---is a bet on the match being exact.

}

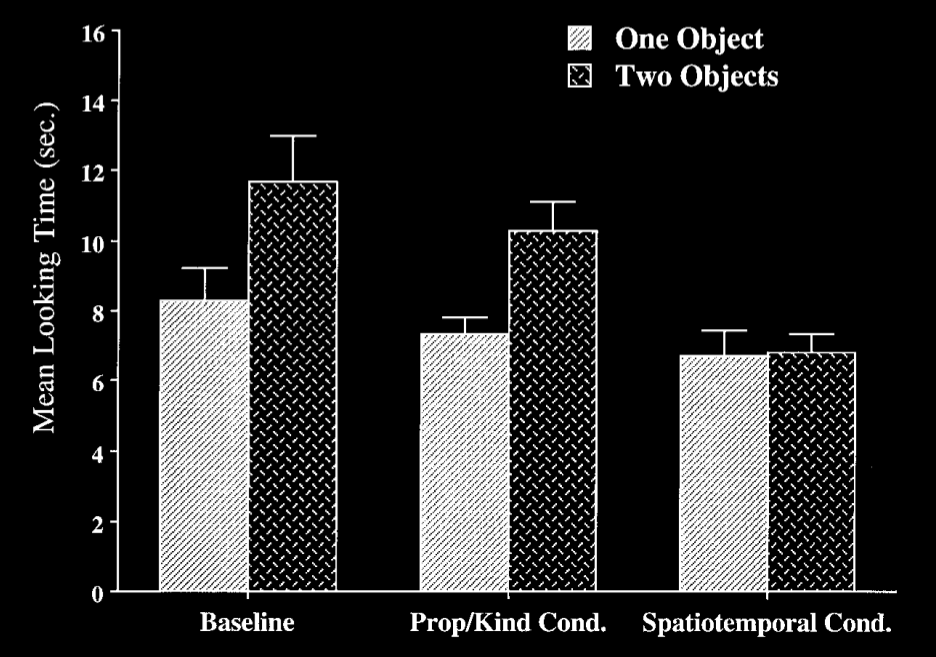

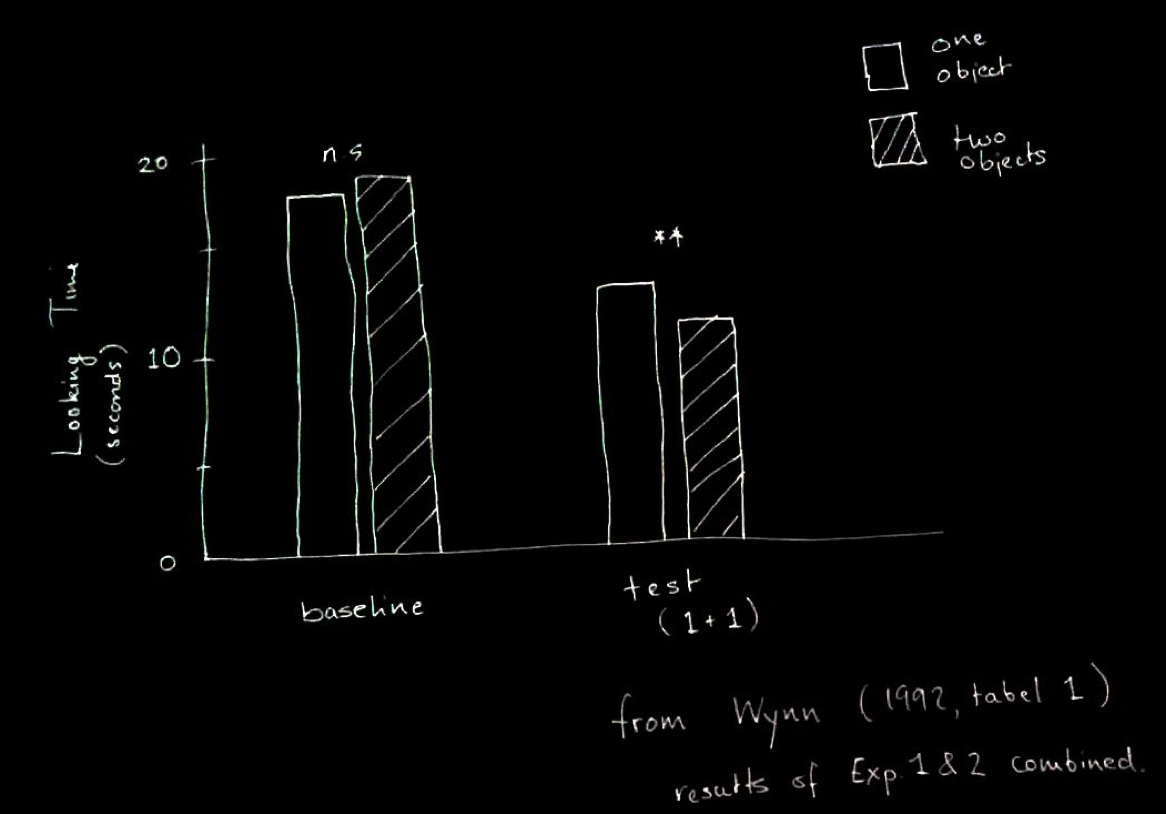

Here are the results.

The central column shows that infants looked longer when they saw

two objects at test rather than when they saw a single object.

This is not different from how they performed in a base line condition

when the information about number was not present.

And it is different from how they performed in the ‘spatiotemporal

condition’ in which the two objects were at simultaneously

visible at one point before the test phase.

While I wouldn’t want to suggest that the evidence on

siganture limits is

decisive, I think it does motivate considering the hypothesis and its

consequences.

In what follows I will assume the hypothesis is true:

infants’ abilities

to track briefly occluded objects depend on a system of

object indexes.

The hypothesis has an advantage which I don’t think is widely

recognised.

This is that object indexes are independent of beliefs and knowledge

states.

Having an object index pointing to a location is not the same thing

as believing that an object is there.

And nor is having an object index pointing to a series of locations over time

is the same thing as believing or knowing that these locations

are points on the path of a single object.

Further, the assignments of object indexes do not invariably give rise

to beliefs and need not match your beliefs.

To emphasise this point, consider once more this scenario

in which a patterned square disappears behind the barrier; later a

plain black ring emerges. You probably don't believe that they are

the same object, but they probably do get assigned the same object index.

Your beliefs and assignments of object indexes are inconsistent in this

sense: the world cannot be such that both are correct.

So assignments of object indexes can conflict with beliefs.

Why is this an advantage?

At the start of this talk I emphasised the variety of evidence

which shows that infants, from four months of age or earlier,

can track briefly occluded objects.

However there is also a substantial body of evidence which suggests that

infants of this age, and even infants who are several months older,

systematically fail to search for briefly occluded objects.

To illustrate, consider an ingenious experiment by \citet{Shinskey:2001fk}.

There was an opaque screen that could rotate between lying flat on the ground and being raised to conceal a toy behind it.

\citeauthor{Shinskey:2001fk} also used a second piece of apparatus just like the first except that the screen was transparent rather than opaque.

They reasoned that infants would quite often pull the screen forwards just for fun, regardless of what is behind it.

However, they also guessed that when infants know there is an interesting toy behind the screen, then they will pull it forwards more often than when they know that there is nothing behind the screen.

This is just what happened when infants were presented with the apparatus involving a transparent screen:

they sometimes pulled the screen forwards when there was no toy behind it, but they pulled it forwards significantly more often when the toy was behind it.

What happened when infants were presented with the opaque screen?

Here infants pulled the screen forwards no more often when they had observed a toy being placed behind it then when they had observed that there was nothing behind it.

This is evidence that seven-month-old infants do not know that a toy they have very recently seen hidden behind a screen is behind the screen.

After all, since knowledge guides action we would expect infants who know that a toy is behind an opaque screen to pull the screen forward more often than infants who know there is nothing behind the screen, just as they do when the screen is transparent.

More than two decades of research strongly supports the view that

infants fail to search for objects hidden behind barriers or screens

until around eight months of age \citep[p.\ 202]{Meltzoff:1998wp} or

maybe even later \citep{moore:2008_factors}.

Researchers have carefully controlled for the possibility that infants’

failures to search are due to extraneous demands on memory or the

control of action.

We must therefore conclude, I think, that four- and five-month-old

infants do not have beliefs about the locations of briefly occluded

objects.

It is the absence of belief that explains their failures to search.

Because this point is controversial, I want to mention one further

piece of the puzzle.

Five-month-olds not only sometimes fail to search for hidden objects but

also sometimes fail to look longer when a momentarily hidden object fails

to reappear as if by magic.

Infants will reach for an object hidden in darkness \citep[e.g.][]{jonsson:2003_infants}.

But what happens if instead of measuring reaching we measure looking times?

\citet{charles:2009_object} compared what happens when an object is momentarily hidden behind a screen with what happens when an object is momentarily hidden by darkness.

They used a trick with light and mirrors so that for some of the infants, the object did not reappear when the screen came up or the light returned.

Surprisingly, five-month-old infants’ looking times indicated that an expectation had been violated only when the object was hidden behind a screen but not when hidden by darkness.

I think this pattern of findings is good evidence against the hypothesis

that four- or five-month-olds have beliefs about, or knowledege of,

the locations of

unperceived objects.

After all,

a belief is essentially the kind of state that can inform actions of any

kind, whether they involve looking, searching with the hands or anything

else.

So this is a virtue of the hypothesis that four- and five-month-old

infants’ abilities

to track briefly occluded objects depend on a system of

object indexes.

Since assignments of object indexes do not entail the existence of

corresponding beliefs,

the fact that infants of this age systematically

fail to search for briefly occluded objects is not an objection to the

hypothesis.

But the hypothesis does face a significant challenge ...

As I said at the start of this talk, infants’ abilities to track briefly

occluded objects are manifested in several different ways.

They are manifested in (iii) anticipatory looking, (ii) reactions

indicating the violation of an expectation, and (i) dishabituation

indicating interest in certain stimuli.

Can all of these behaviours be explained merely by invoking object

indexes?

This is an important question for me so I want to pause to emphasise it.

This question is, What can the operations of a system of

object indexes explain?

The primary functions of object indexes include influencing the allocation

of attention and perhaps guiding ongoing action.

If this is right, it may be possible to explain anticipatory looking

directly by appeal to the operations of object indexes.

But the operations of object indexes cannot directly explain differences

in how novel things are to an infant.

And nor can the operations of object indexes directly explain why infants

look longer at stimuli involving discrepancies in the physical behaviour

of objects.

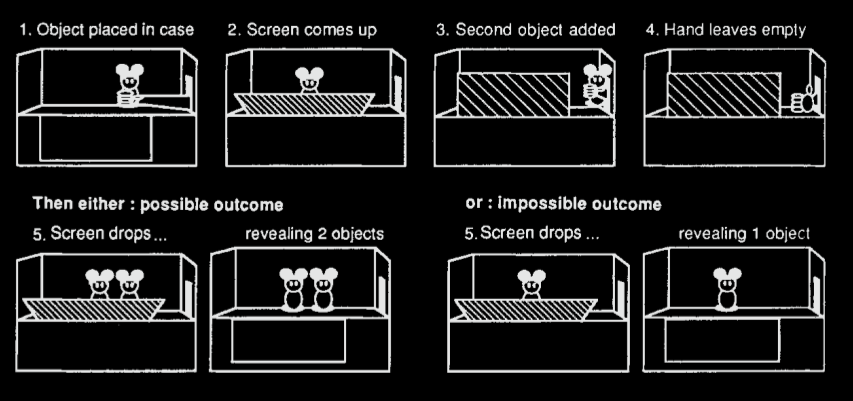

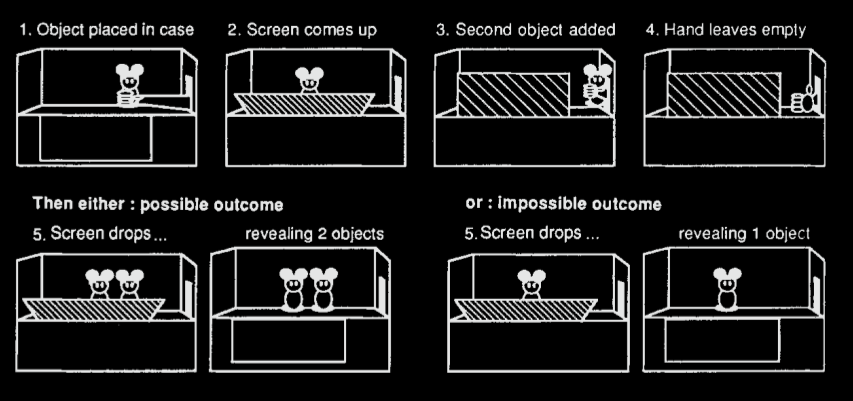

To illustrate this point, consider this famous violation-of-expectations

experiment by \citet{wynn:1992_addition}.

Her subjects were five-month-olds.

We know that infants are likely to maintain object indexes for the two

mice while they are occluded.

Accordingly, when the screen drops in the condition labelled

‘impossible outcome’, there is an interruption to the normal

operation of object indexes: infants have assigned two object indexes

but there is only one object.

But why does this cause infants to look longer at in the

‘impossible outcome’ condition than in the ‘possible outcome’ condition?

How does a difference in operations involving object indexes result

in a difference in looking times?

Here you see the results.

The looking times are always over 10 seconds, and infants look

more than a second longer (mean looking time) at the impossible event.

How could the operations of object indexes cause this difference?

An initially appealing move would be to add would be beliefs.

That is, it would be natural to say that assignments of object indexes

give rise to corresponding beliefs, and these beliefs in turn explain

facts about what appears novel or strange.%

\footnote{

I guess many researchers do think that this, or something like it, is

true.

For instance, \citet{Leslie:1998zk} present their hypothesis as a

view about infants’ object \emph{concept}.

}

But we’ve just seen that this view is almost certain to be wrong

because it generates incorrect predictions about infants’ manual

searching.