Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Commentary on Wolfgang

Prinz and Michael Graziano

s.butterfill@warwick.ac.uk

Q1

What about us?

‘minds [are] open systems whose basic makeup is determined through social interaction and communication’

Prinz (2012, p. 33)

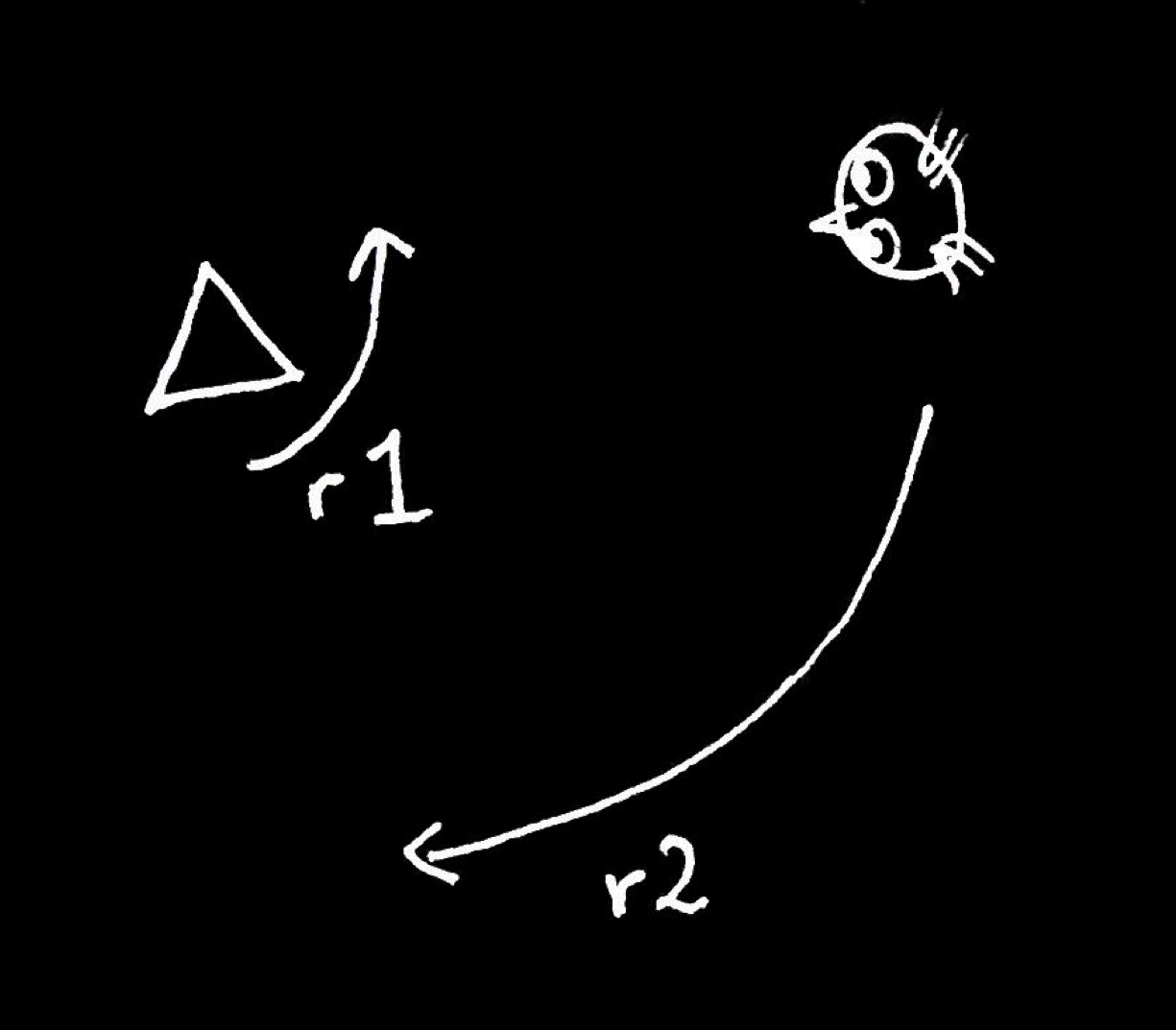

| from | to | label |

| me | you | export |

| you | me | import / open minds |

| us | me you | ? |

‘the will as an individual device to serve ...’ ‘the requirements of collective control’

Prinz (2012, p. 137)

common coding

‘a shared space of representation that uses the same set of representational dimensions for coding one’s own action and foreign perception’

Prinz (2012, p. 67)

Q2

What about kids?

(1) ‘my brain [...] constructs a set of information, A, that allows me to conclude that I am aware of the content [X].’

Graziano (2013, p. 70)

(2) ‘awareness is an attention schema.’

Graziano (2013, p. 69)

I.e. ‘the property of awareness is ... a chunk of information, that can be bound to the larger object file.’

Graziano (2013, p. 21)

| 14 months | awarness depends on social relations | Moll & Tomasello (2007) |

| 2 years | blindfolds prevent awareness even if not worn during the critical event | Dunham et al (2000); cf Poulin-Dubois et al (2007) |

| 2.5 years | moving a barrier does not prevent awareness | McGuigan & Doherty (2002) |

(1) ‘my brain [...] constructs a set of information, A, that allows me to conclude that I am aware of the content [X].’

Graziano (2013, p. 70)

(2) ‘awareness is an attention schema.’

Graziano (2013, p. 69)

I.e. ‘the property of awareness is ... a chunk of information, that can be bound to the larger object file.’

Graziano (2013, p. 21)

- one- and two-year-olds’ representations of awareness differ systematically from most adults’

- one- and two-year-olds’ attention schema differs systematically from most adults’

- Conditions under which 1- and 2-year-olds’ are aware of a thing differ systematically from conditions under which most adults are aware of a thing.

Q3

What about phenomenology?

‘the self-from-others framework is silent on issues pertaining to qualitative aspects of mental experience’

Prinz (2012, p. 239 fn. 14)

What is like you?

‘subjectivity is an artefact made by humans ... People have a self in the same sense as they have ... money, courts of law, or governments.’

Prinz (2013, p. 1111)

‘there is no subjective feeling ... [i]nstead, there is a description of having a feeling’

Graziano (2013, pp. 21-2)

‘the hearer who hears must also be entailed in the act ... the hearing of that tone is hardly conceivable without a mental self, or subject, who hears.’

Prinz (2012, p. 13)

- EITHER The implicitly specified perceiver is merely ‘an artefact made by humans’, a consequence of Like You or the attention schema.

- OR Appeal to Like You and an Attention Schema can explain how things become explicit; but they cannot explain the ways in which a subject of awareness is implicitly specified.

Q4

What about objectivity?

How am I able to think demonstrative thoughts about this green apple?

- Someone described it to me

- I have visually expeirenced it

- ...

‘strictly speaking you are not deciding and reporting on the rock itself. You are deciding and reporting on the information constructed in your visual system.’

Graziano (2013, p. 47)

‘intuition of mental access’

Prinz (2012, p. 201)

S + A + X

Not every experience enables demonstrative thoughts about the thing experienced.

visual experience of a green apple

auditory experience of a tone

the sensation of being stung by a nettle

the feeling of someone’s eyes boring into your back

the feeling of familiarity

what about ...

us?

kids?

phenomenlogy?

objectivity?

‘Suppose that you are looking at a green object and have a conscious experience of greenness. ...

the brain contains a chunk of information that describes the state of experiencing, and it contains a chunk of information that describes spectral green.

Those two chunks are bound together.

In that way, the brain computes a larger, composite description of experiencing green.’

Graziano (2013, p. 20)

(1) ‘my brain [...] constructs a set of information, A, that allows me to conclude that I am aware of the content [X].’

Graziano (2013, p. 70)

(2) ‘awareness is an attention schema.’

Graziano (2013, p. 69)

S + A + X