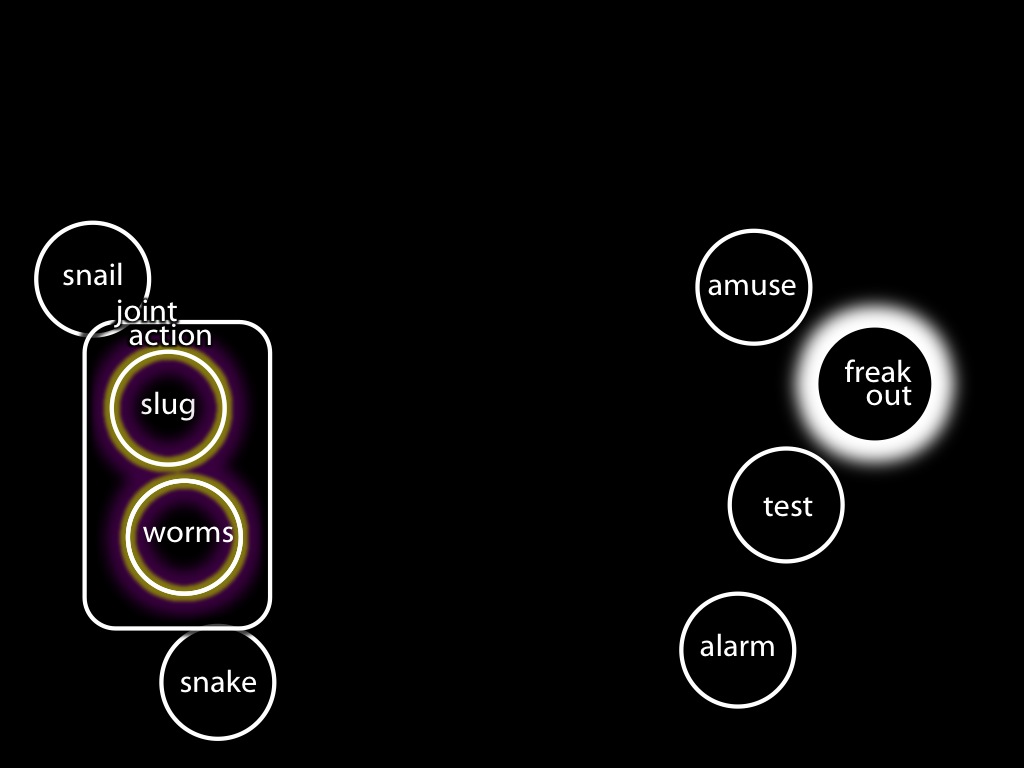

Outcomes are represented motorically not only in performing an action but sometimes also in observing another agent perform that action.

in observing others act

motor planning* for others’ actions occurs

This can happen not only when observing a single agent acting alone but even when observing several agents performing a joint action \citep{manera:2013_time}.

Manera et al (2013)

--- even when several others act jointly ---

These motor representations trigger planning-like processes in the observer much like those that would occur if the observer were actually acting,

and thereby sometimes enable you to anticipate the targets of others’ actions, so that it is almost as if you were covertly anticipating their actions by planning how someone in their situation would proceed \citep{ambrosini:2011_grasping,Costantini:2012fk}.

and enables us to anticipate their actions.

Costantini et al (2013)

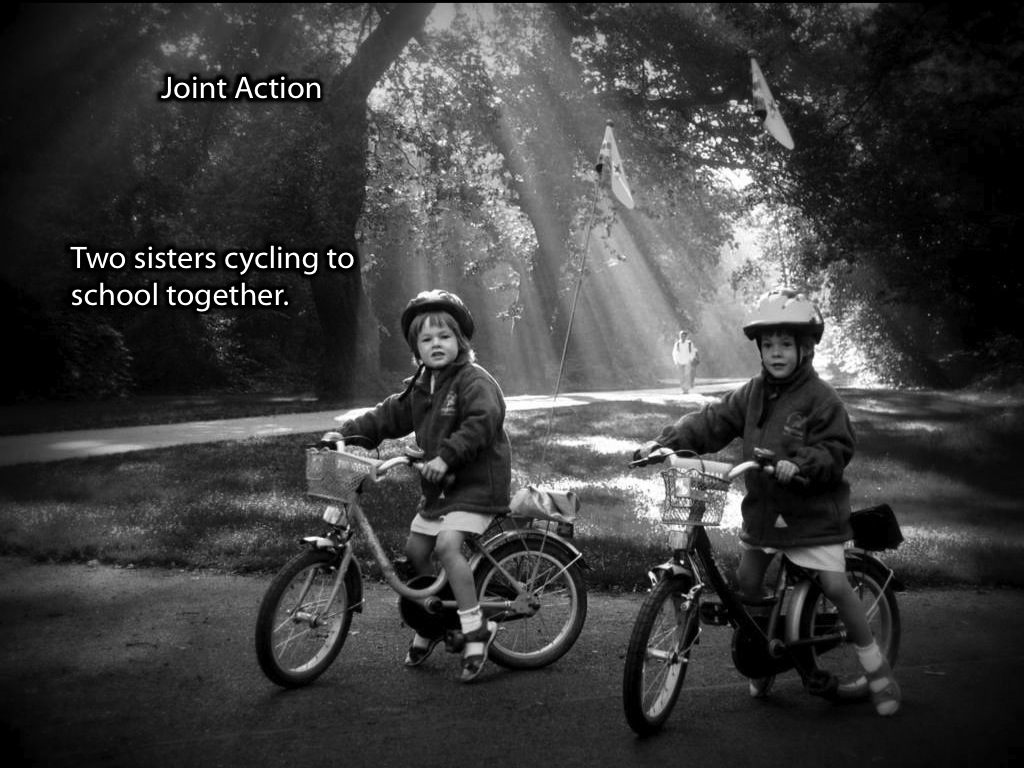

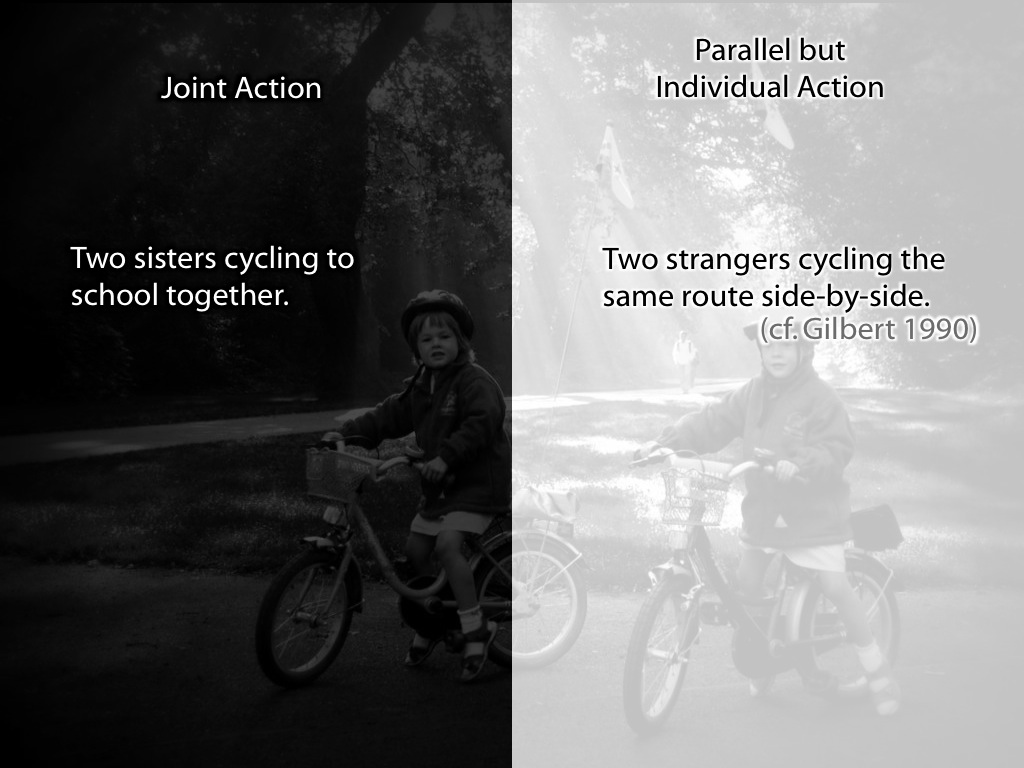

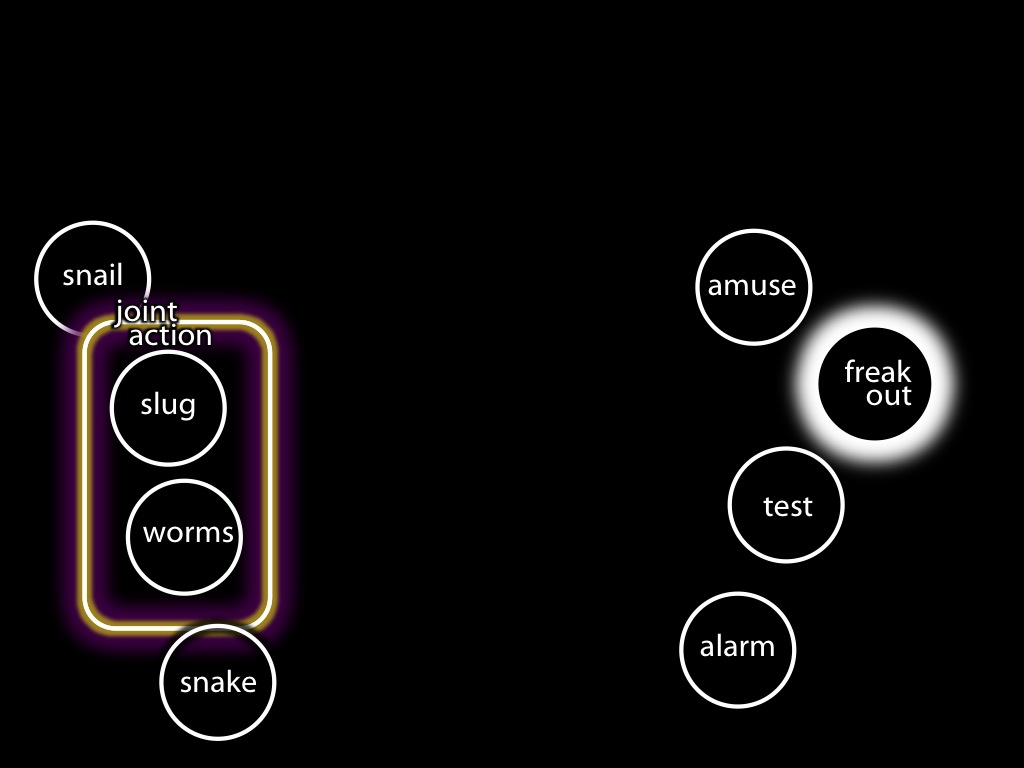

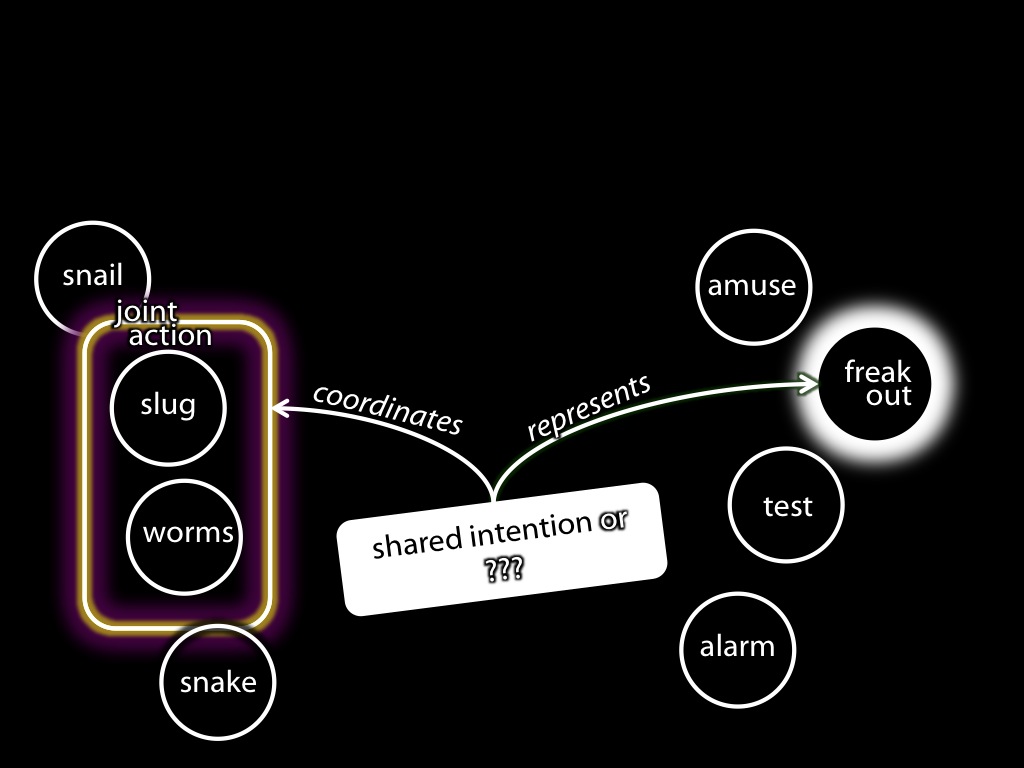

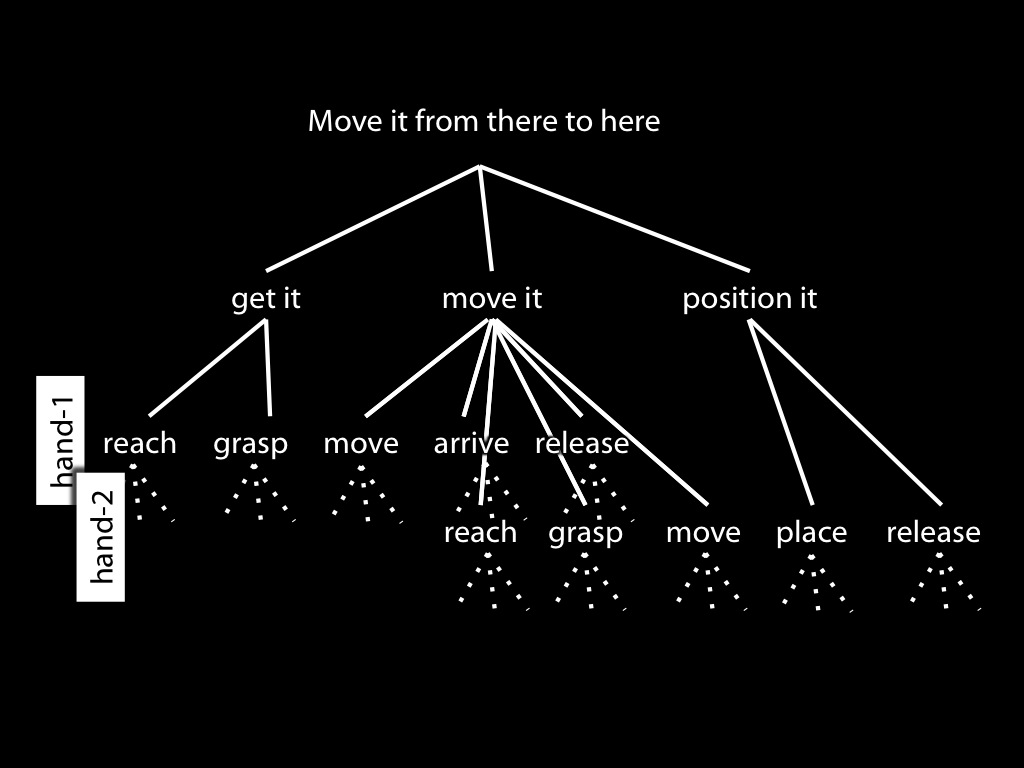

Consider one agent who is engaged in joint action with another:

they are moving a mug from one place to another, passing it between their hands half-way through.

Motor representations concerning outcomes to which the other’s actions are directed,

and the associated planning-like processes,

can occur in these agents \citep{kourtis:2010_favoritism,kourtis:2012_predictive,meyer:2011_joint}.

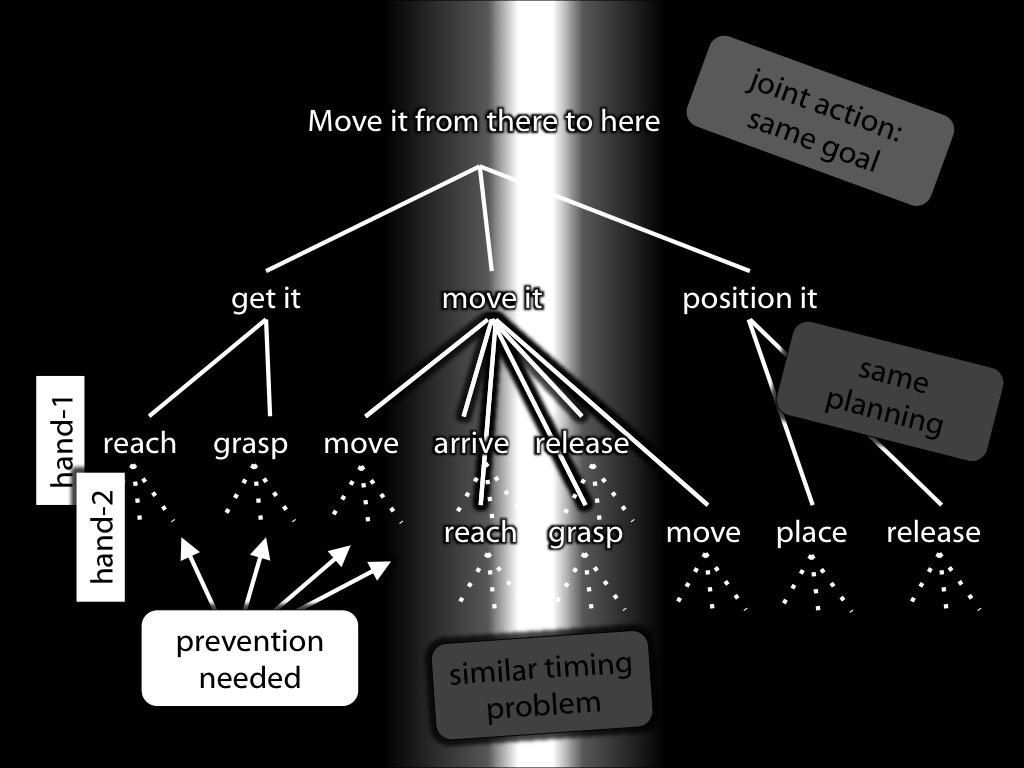

Now these agents engaged in joint action are performing complementary actions.

In general, performing one action while observing (or even imagining) a complementary action produces interference,

and at least some of this interference is probably caused by motor representations related to the observed action \citep{kilner:2003_interference,ramsey:2010_incongruent_}.

Given this, we might guess that

when motor representations concerning the other’s actions occur in joint actions involving complementary actions,

these representations would interfere with the agents’ performance and so impair coordination.

In joint action

Kourtis et al (2010; 2012)

it can also occur

However, it turns out that the opposite is true, at least in some cases.

Motor representations concerning another’s actions can facilitate interpersonal coordination in joint action.

(This is true for a variety of joint actions including passing an object, ballistic actions and playing a piano duet.

(\citealp[p.\ 9]{kourtis:2012_predictive};

\citealp{loehr:2011_temporal};

\citealp{novembre:2013_motor};

\citealp{vesper:2012_jumping};

\citealp{vesper:2013_our}).

But how might motor representations concerning another’s actions facilitate performance in joint action?

Vesper et al (2012);

and informs planning* for our own actions.

Novembre et al (2013)

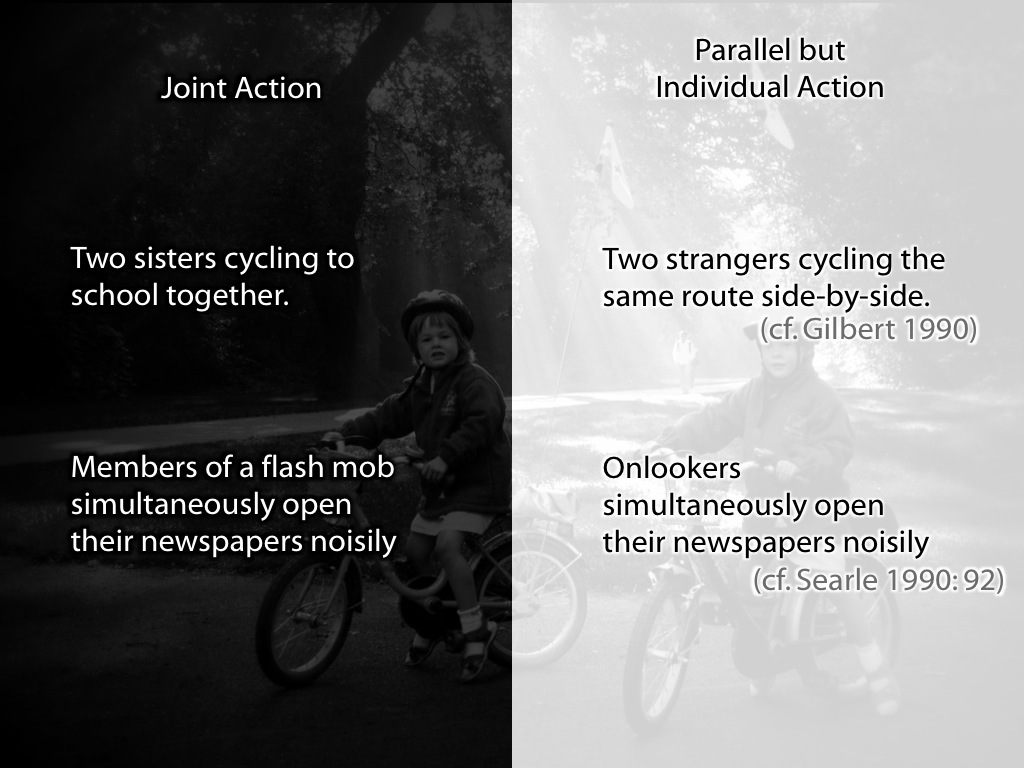

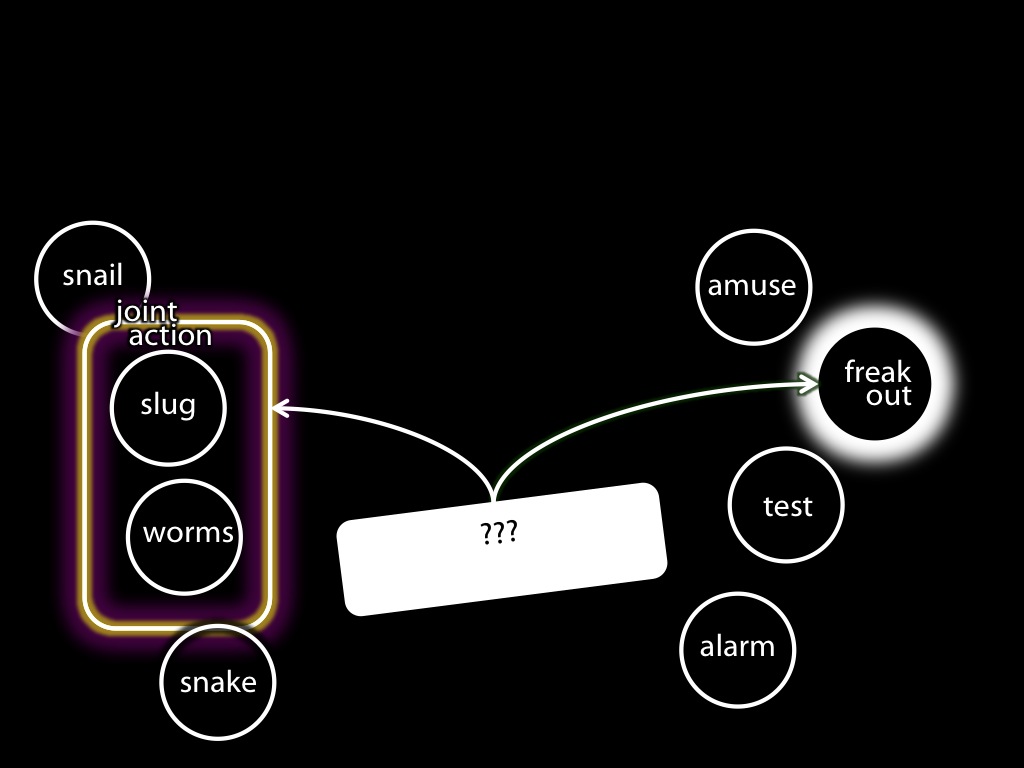

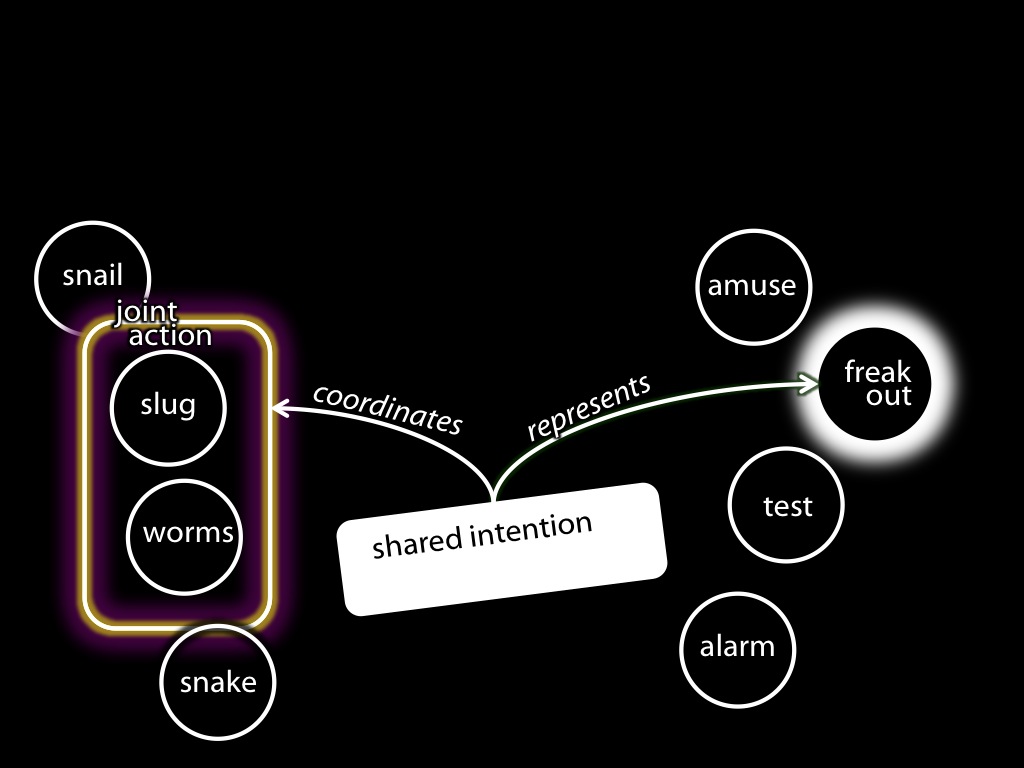

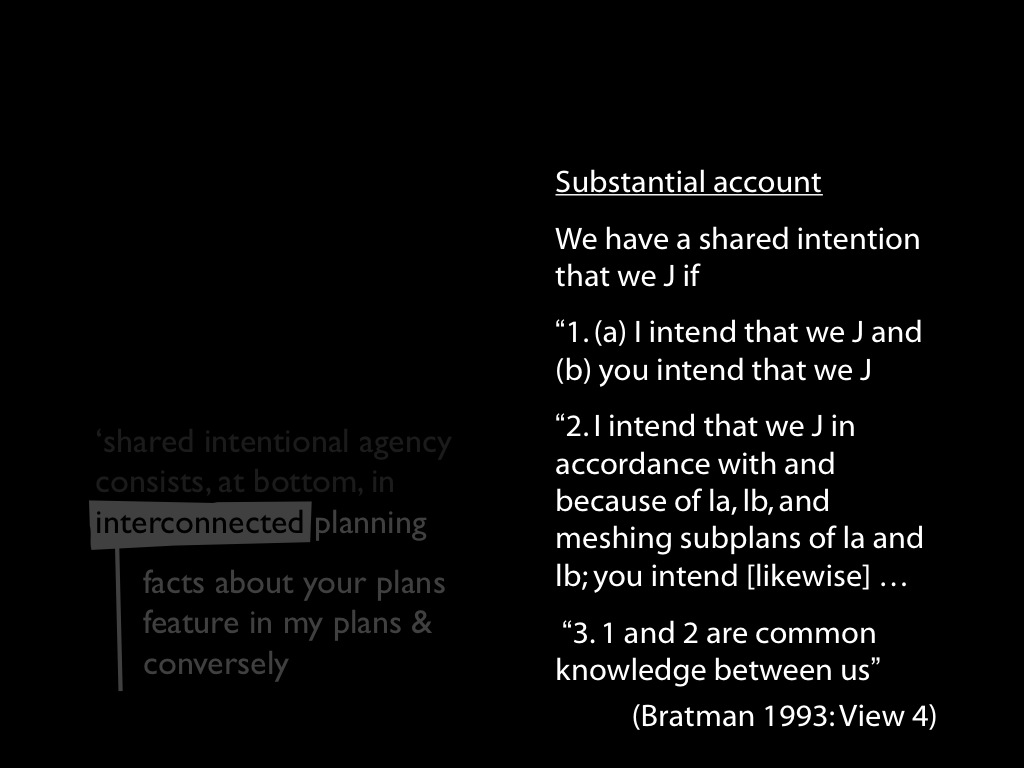

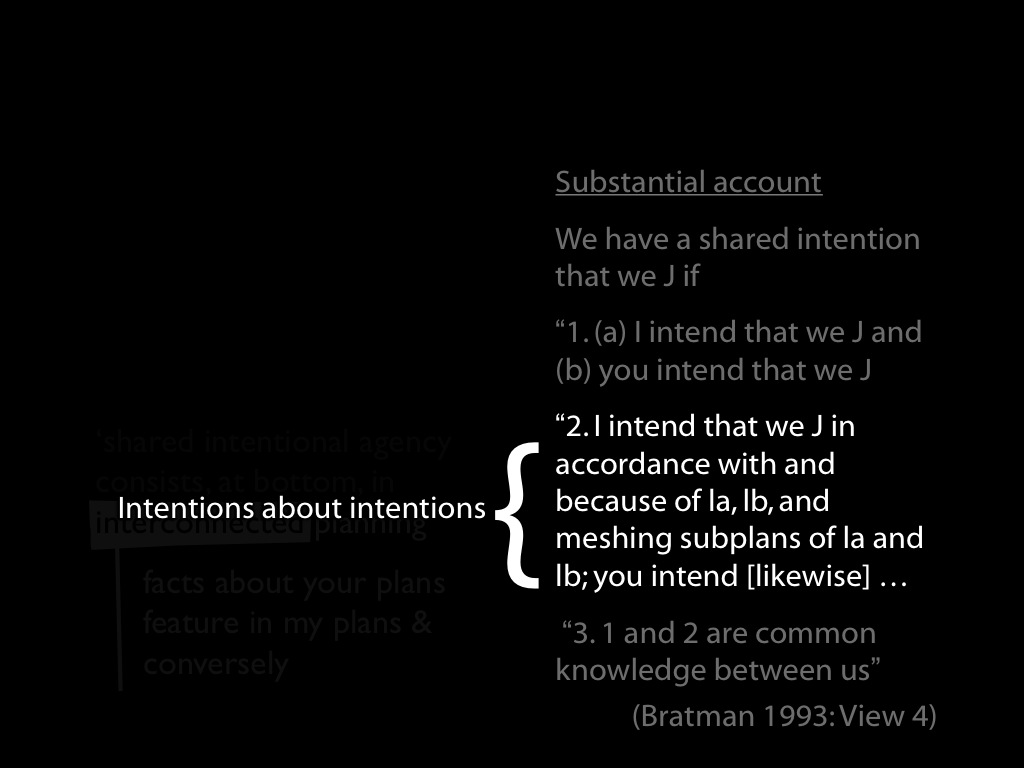

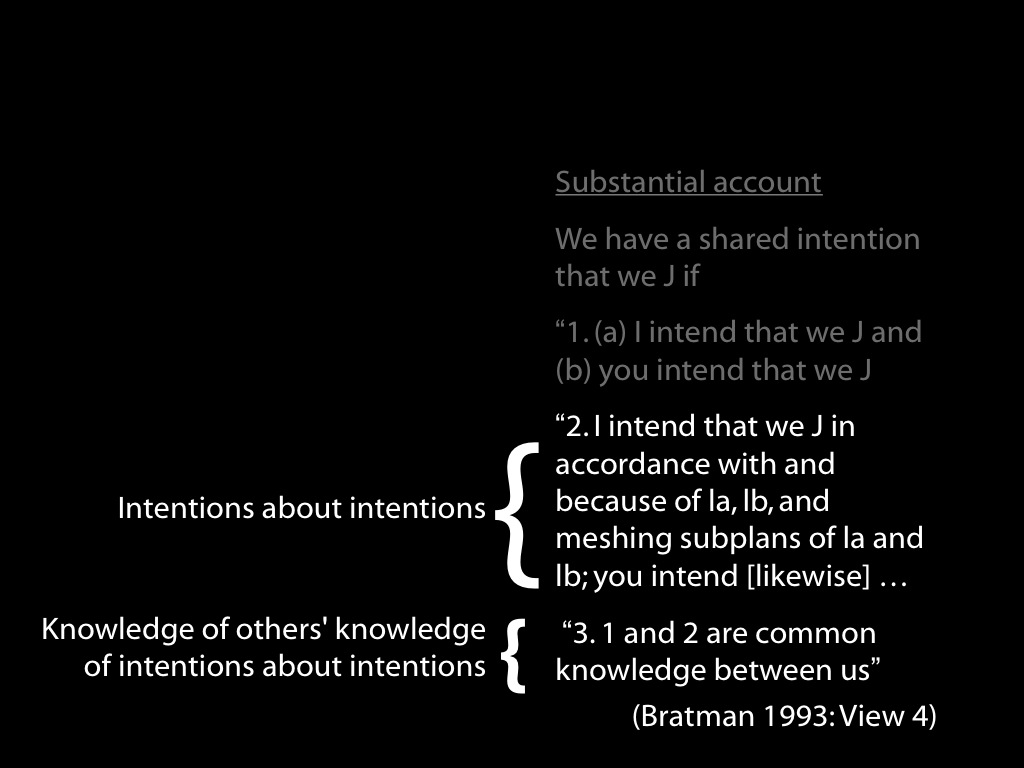

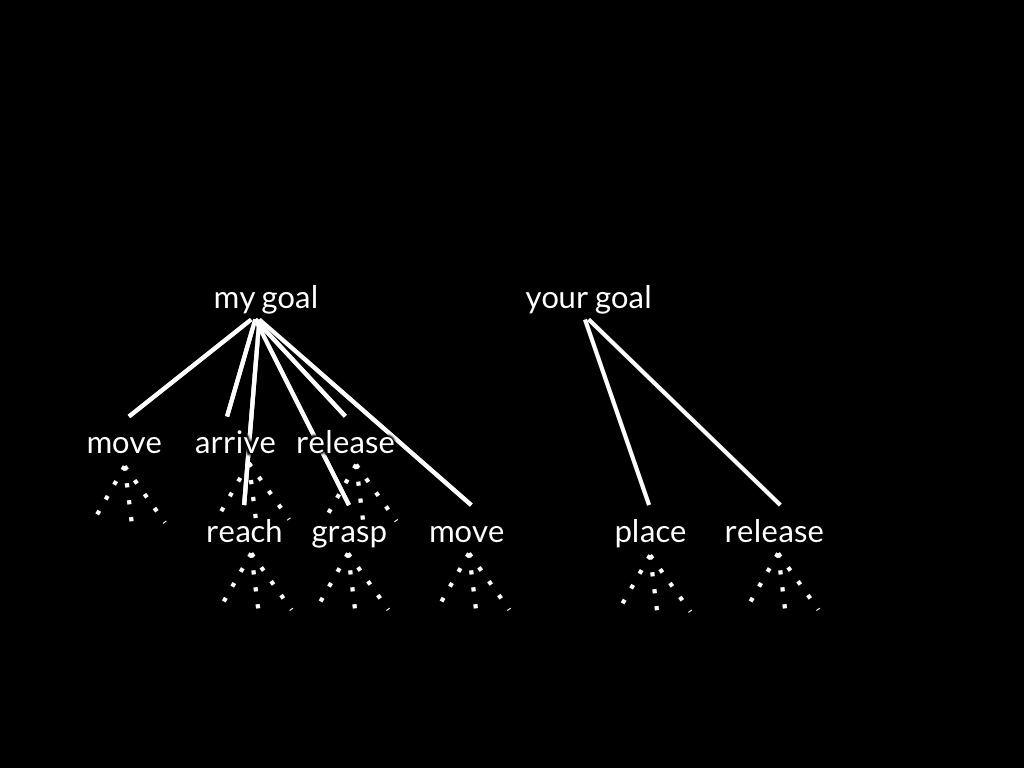

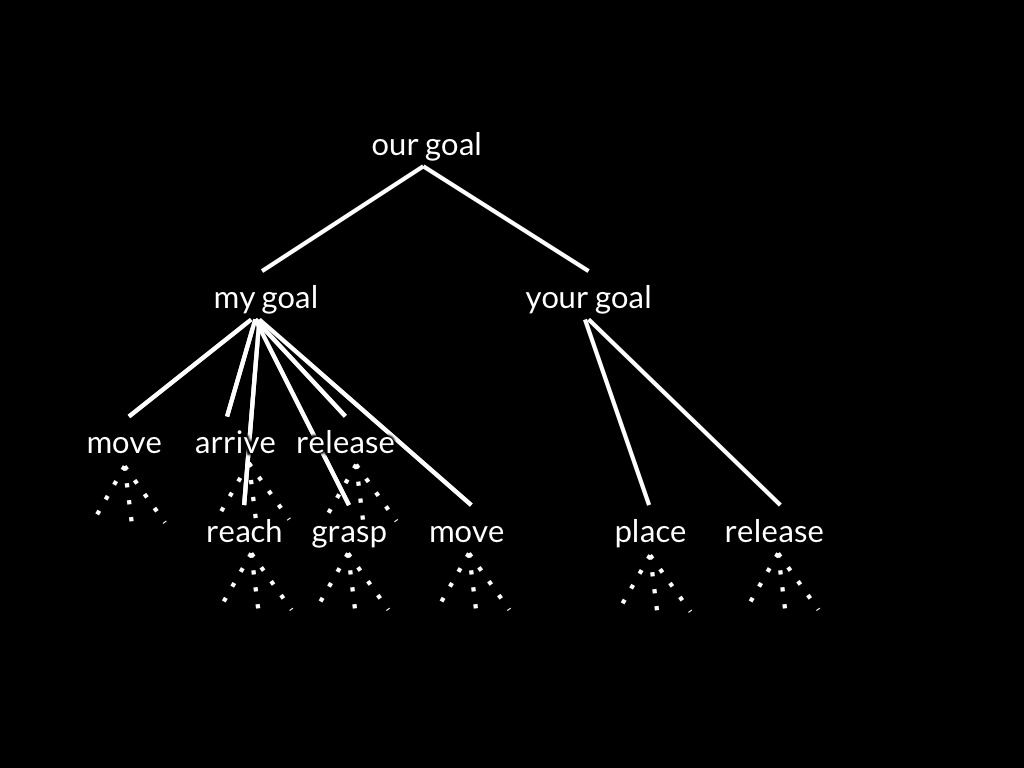

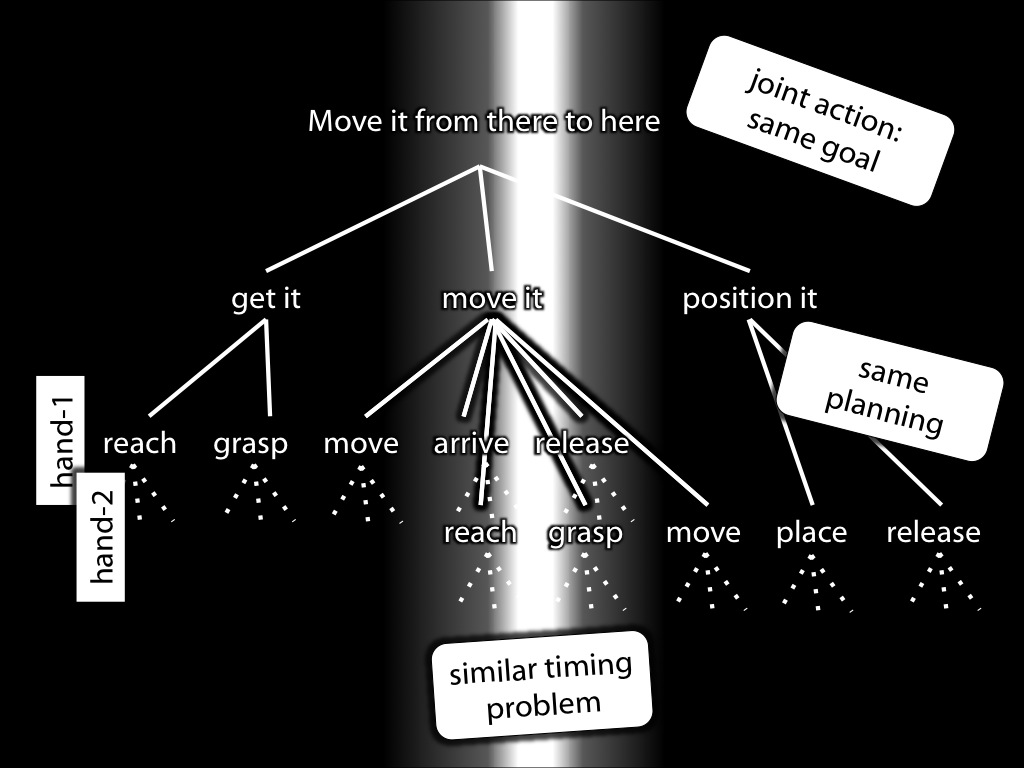

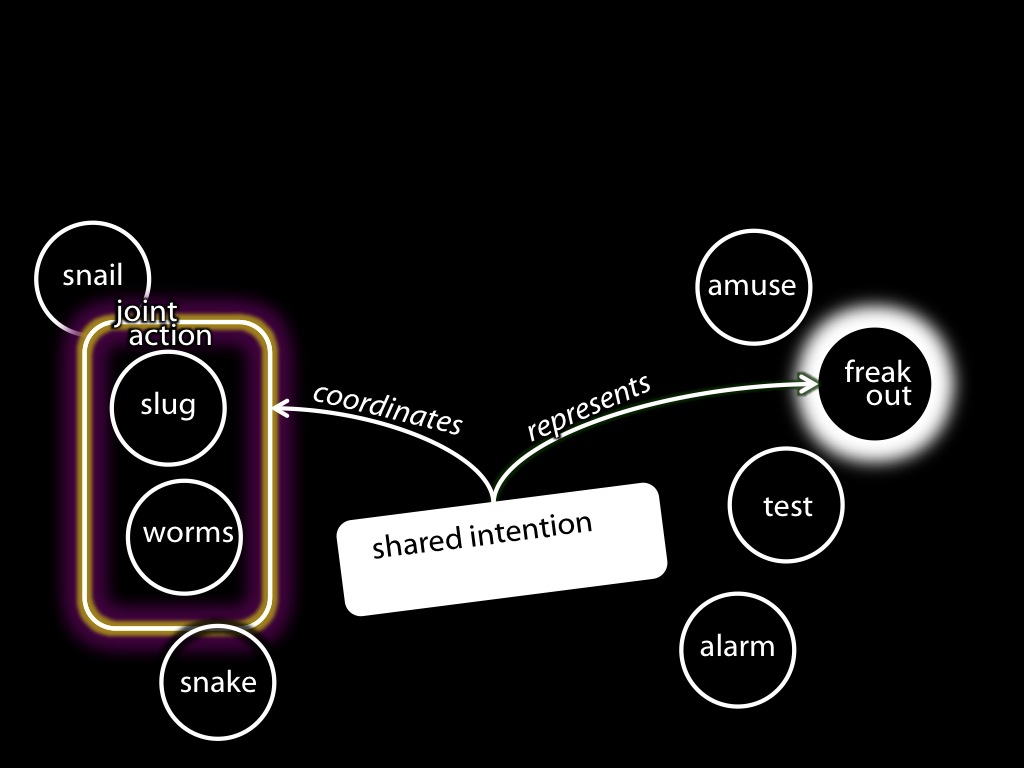

At this point it may be natural to suppose that in joint action

there are two (or more) separate sets of motor representations and processes:

one for your own actions, another for the other’s (or others’)

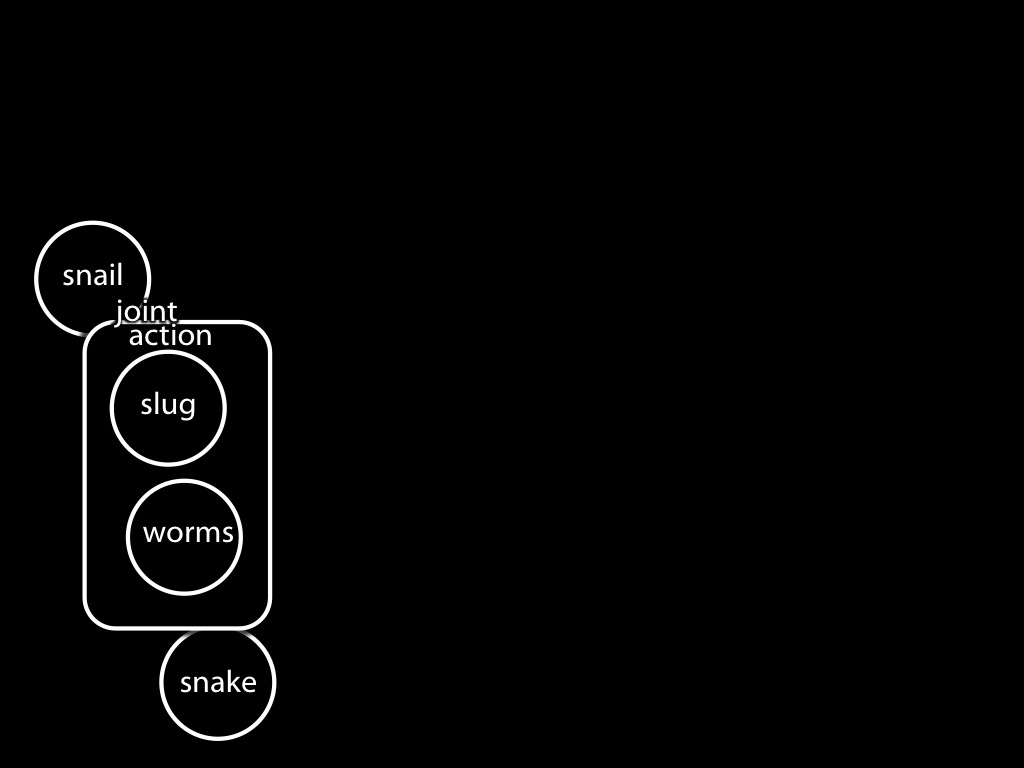

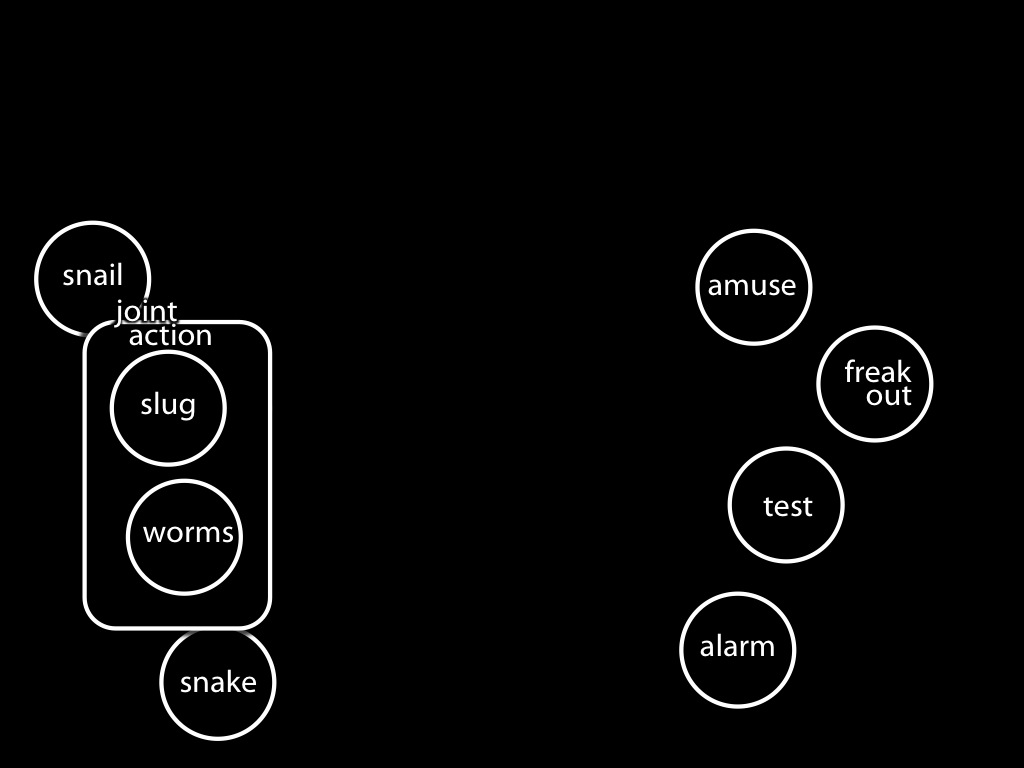

Like this [image of two separate plans].

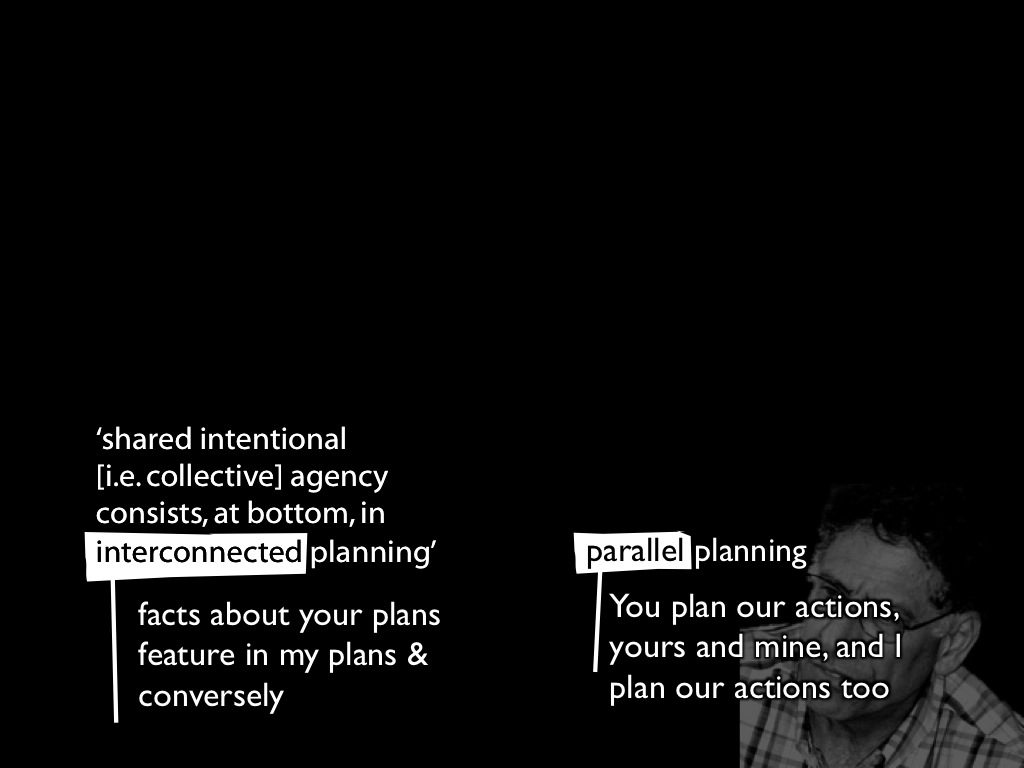

This is indeed how things are in some competitive actions.

In competitive actions there are sometimes planning-like motor processes concerning an opponent’s action as well as concerning your own \citep{sartori:2011_simulation}.

In competitive action

we sometimes plan* the others’ action and then our own.

Sartori et al (2011)

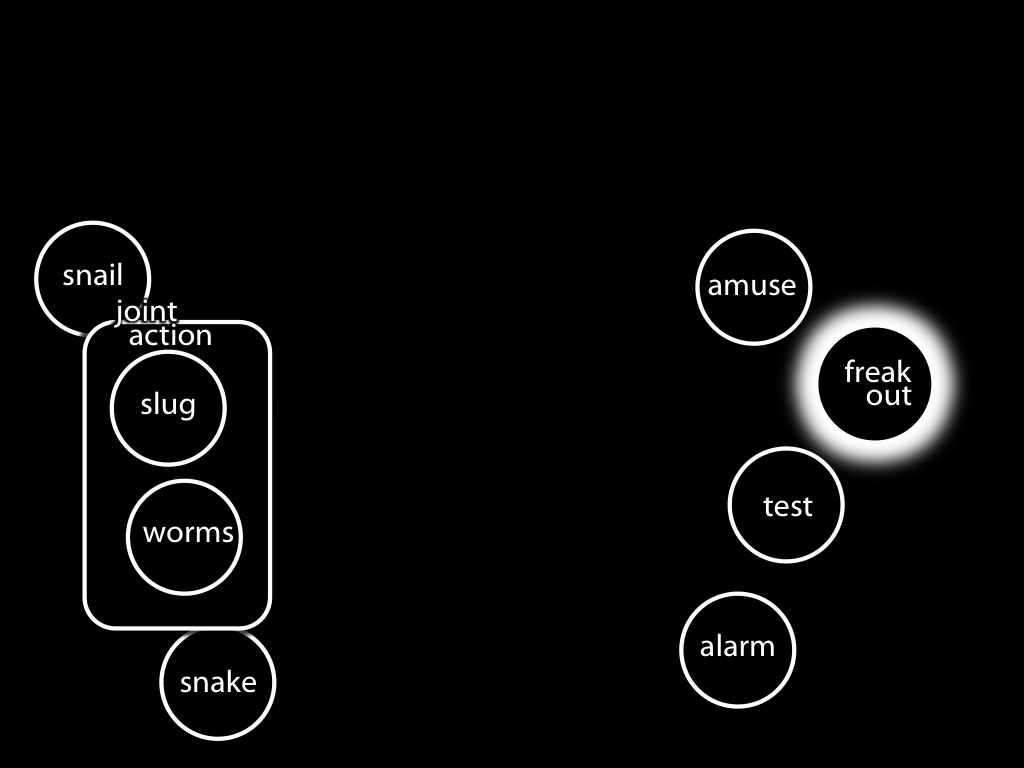

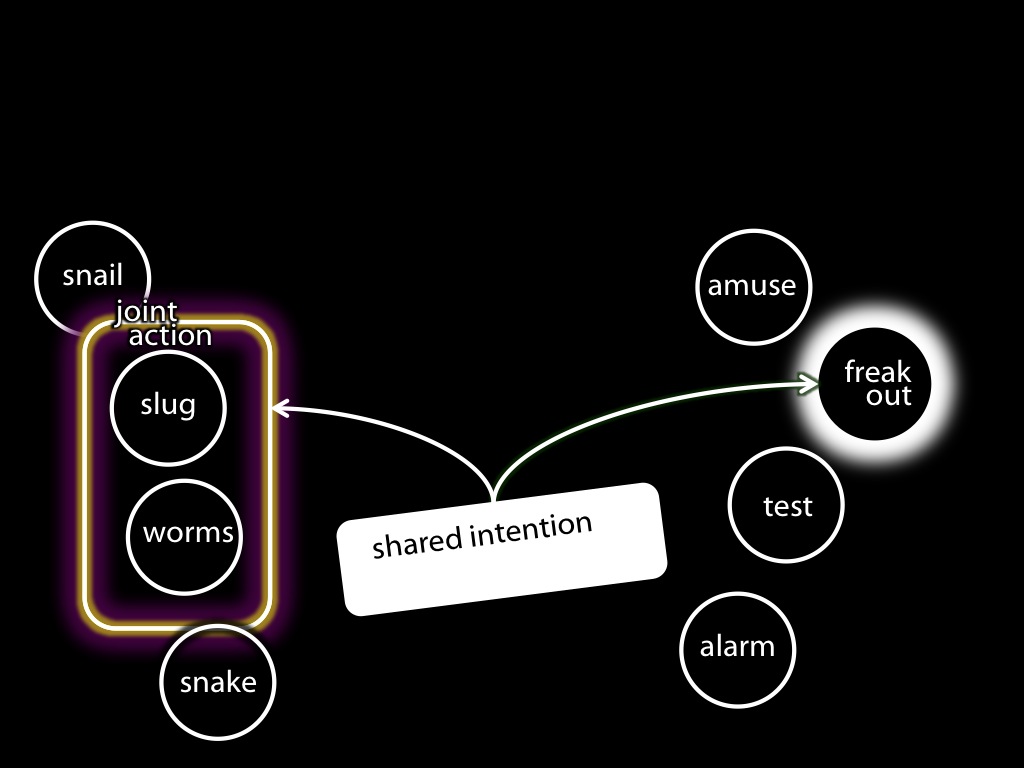

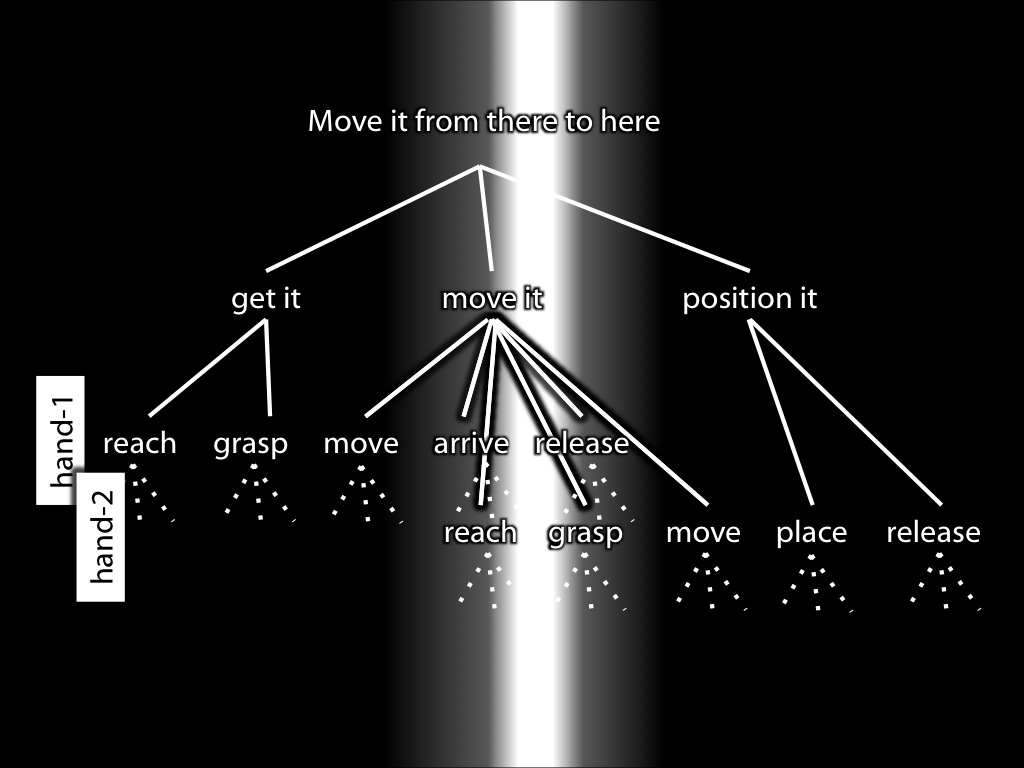

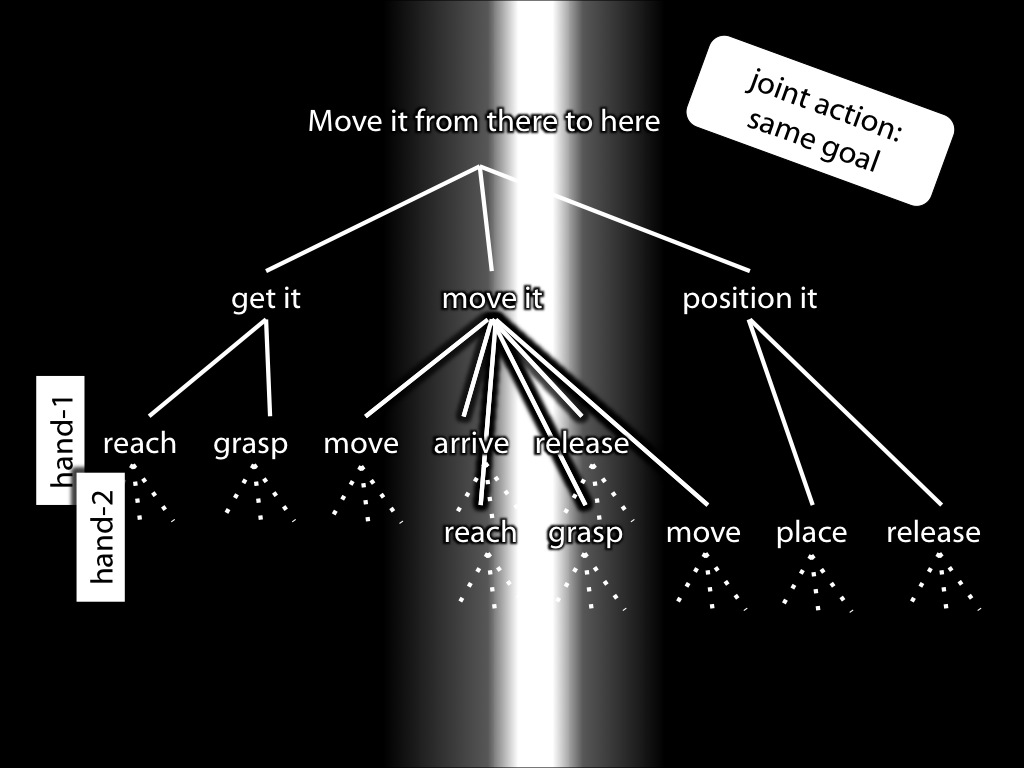

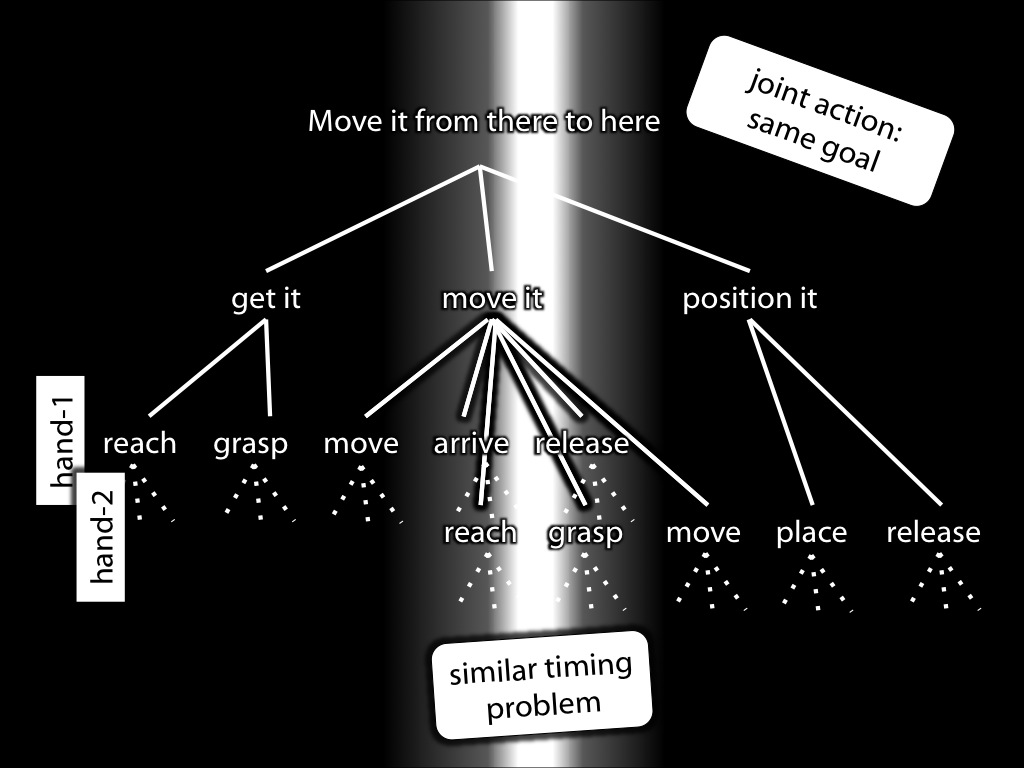

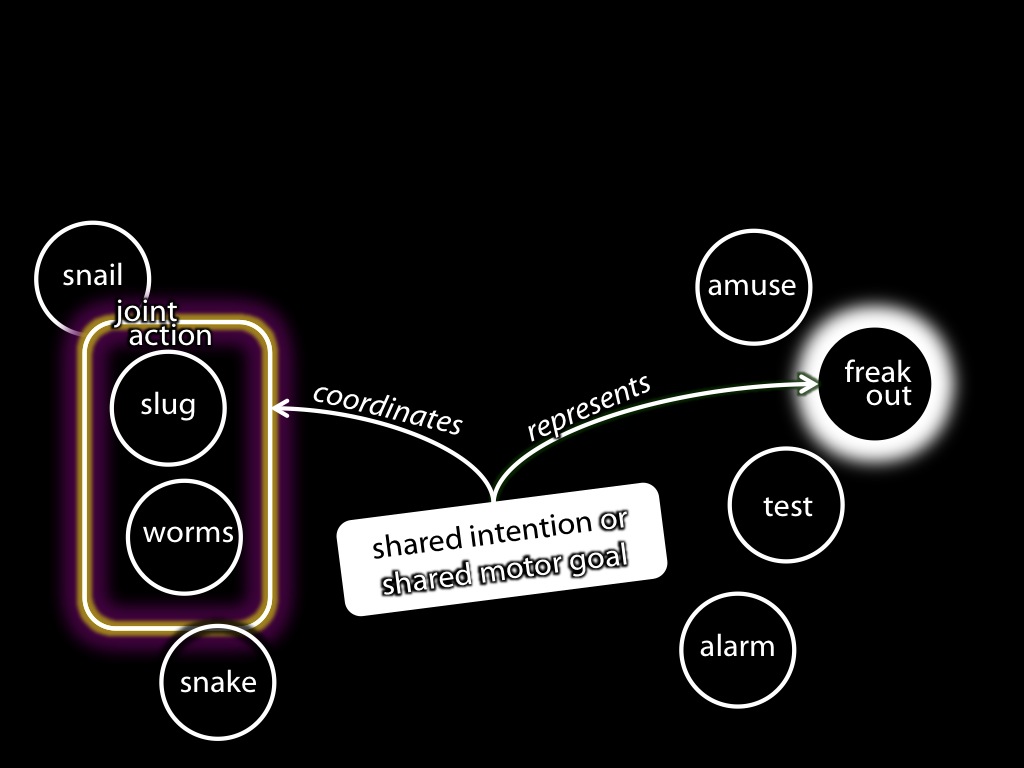

But there is evidence that in some joint actions, a single outcome to which the agents’ actions are collectively directed is represented motorically by each agent \citep{loehr:2013_monitoring,Menoret:2013fk,tsai:2011_groop_effect}.

But in joint action, sometimes

Tsai et al (2011);

there is one goal that we each represent

Loehr et al (2013); Ménoret (submitted); Vesper et al (in prep.)

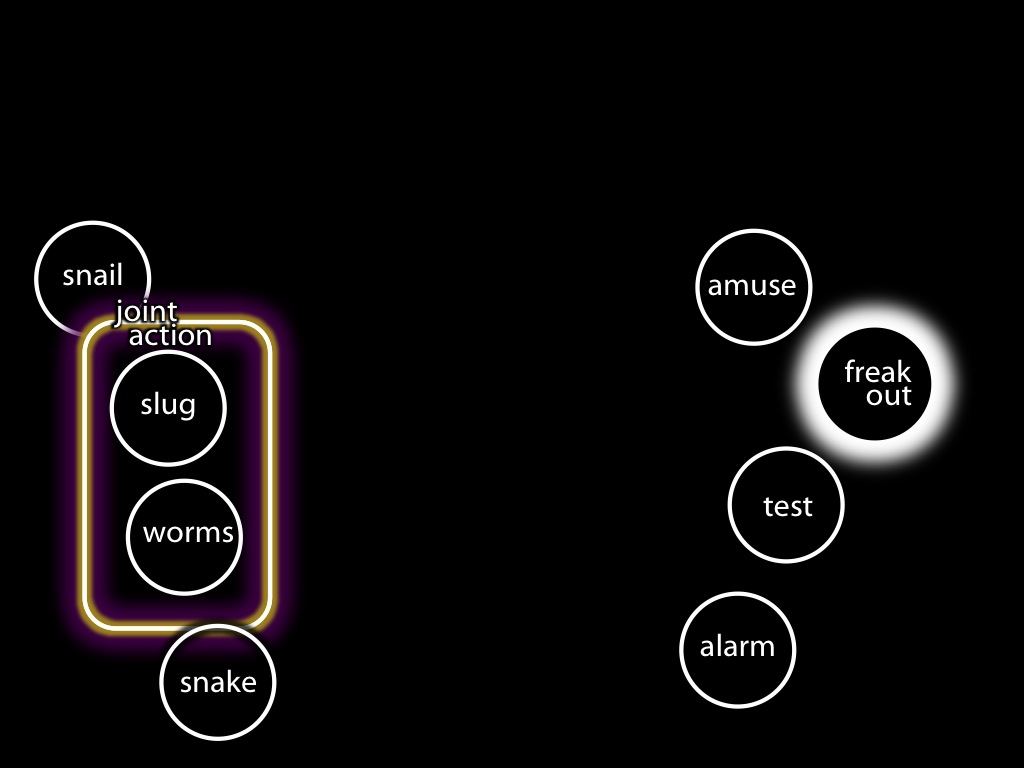

There is also evidence that when agents are engaged in joint action,

they sometimes take into account future actions to be performed by others when choosing how to act now, and do so in much the way they would if they were performing the whole action alone \citep{meyer:2013_higher-order}.

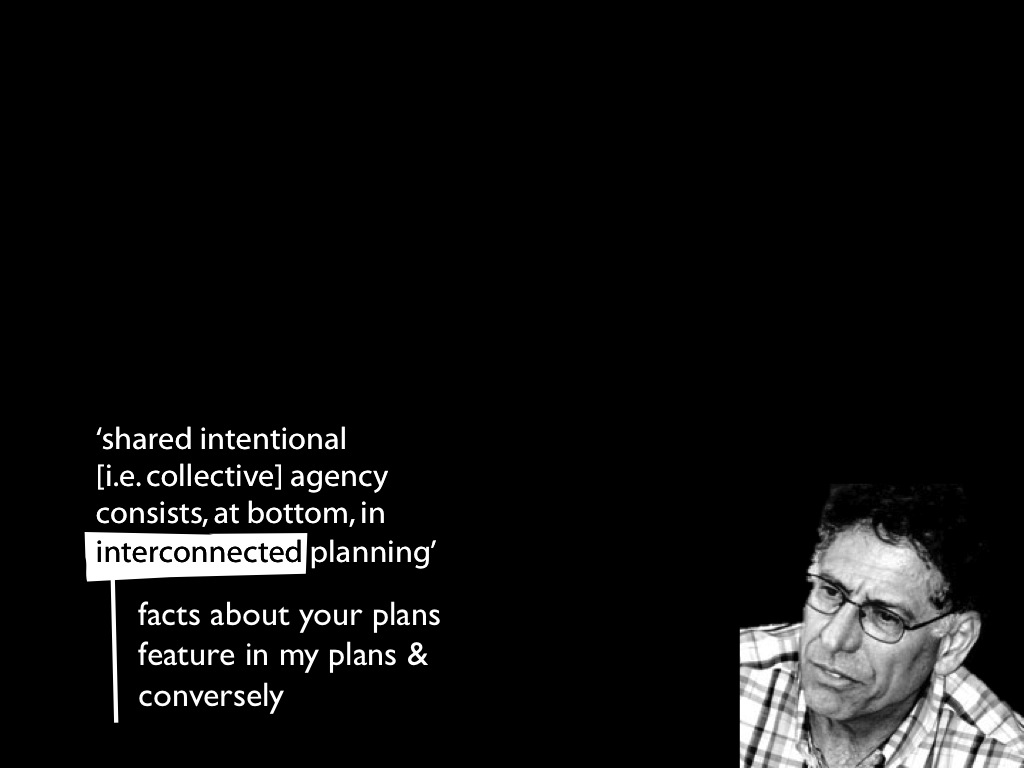

Taken together, this evidence suggests that when an agent is involved in joint action, there is sometimes a single plan-like structure of motor representations concerning both her own and the others’ actions.

\textbf{In joint action, it is sometimes almost as if we each engage in motor planning for all of our actions.}

and we each make a single plan* for both of our actions

Meyer et al 2013

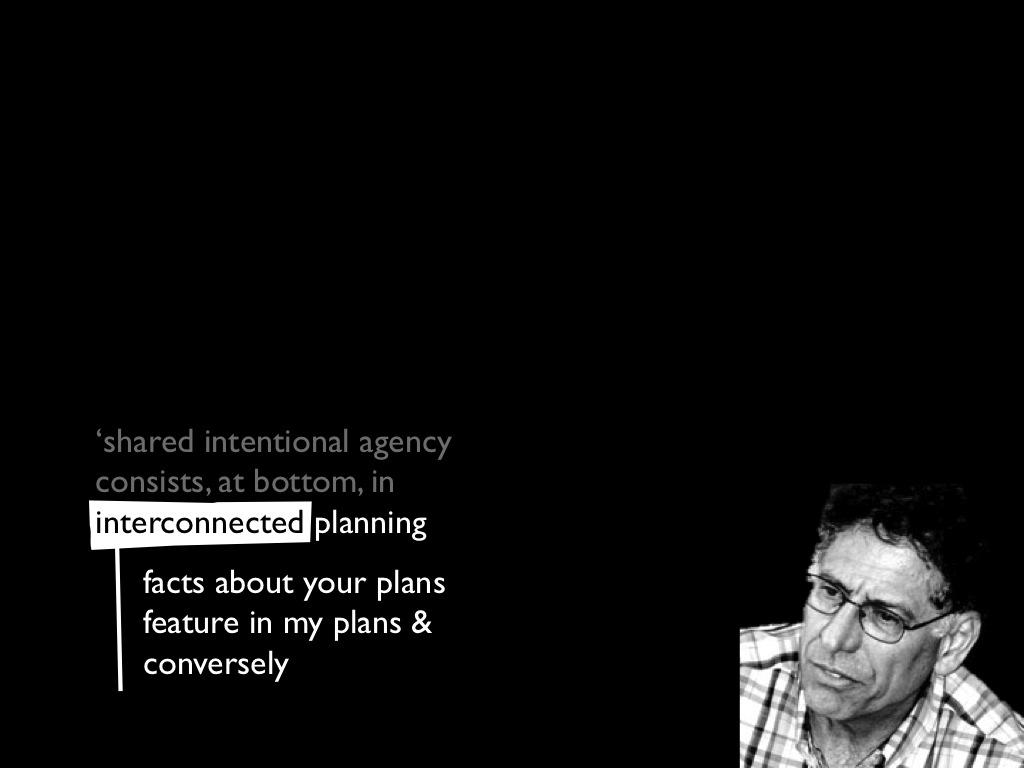

This idea---that there may sometimes be a single plan-like structure of motor representations concerning both your own and others’ actions---can easily seem incoherent. This is because it involves, or at least flirts with, the idea that in joint action, each agent plans others’ actions as well as her own.

But how is this possible without irrationality or ignorance?

How could one agent rationally plan another's actions knowing that she can't control them?%

\footnote{

This objection is due to Wolfgang Prinz (personal communication).

}