Home >> Talks >>

Joint Action and the Emergence of Mindreading

by Stephen A. Butterfill

Handout and Slides

Download: handout [pdf] and slides [pdf]

Abstract

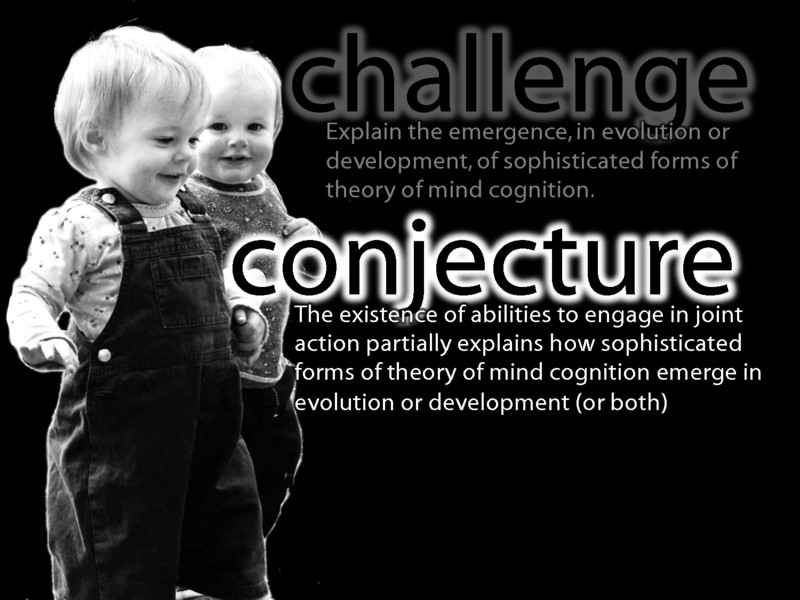

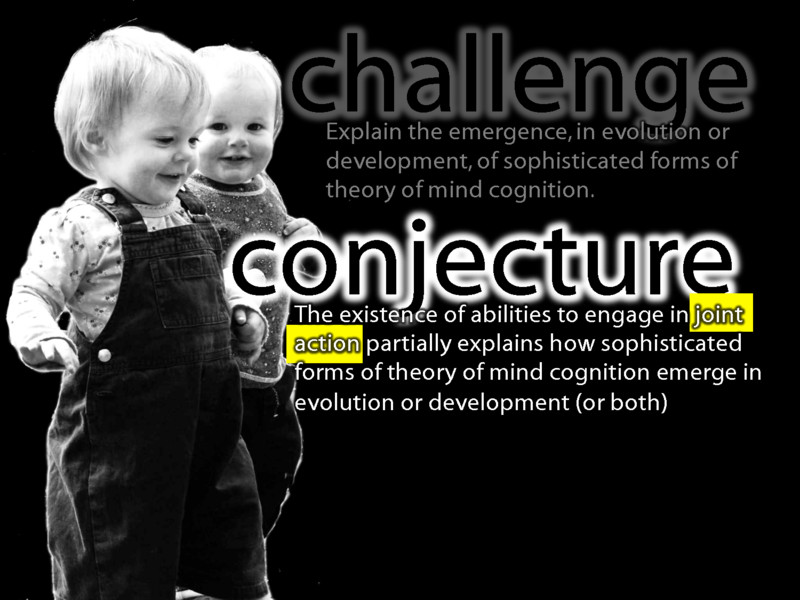

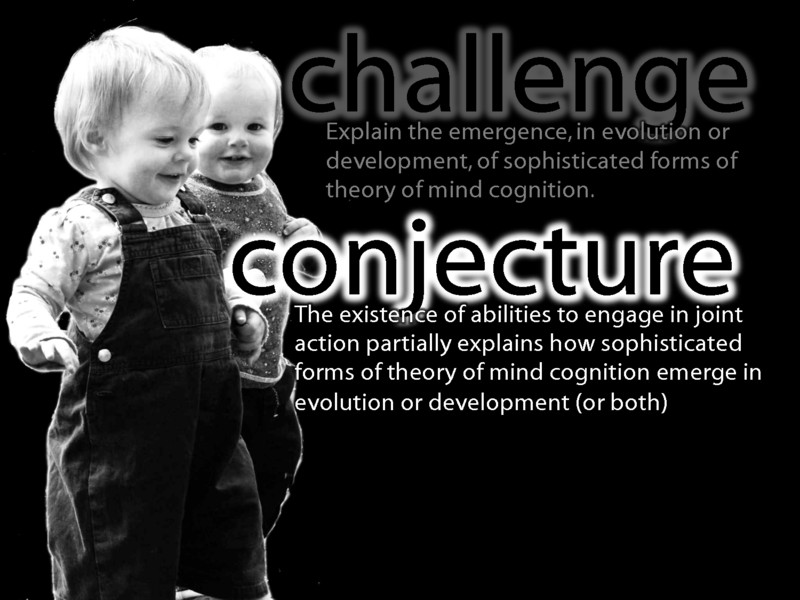

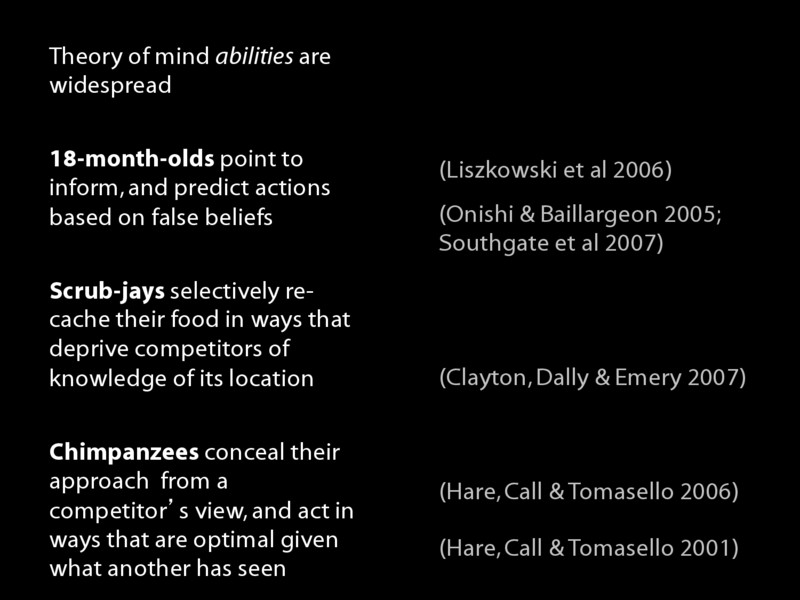

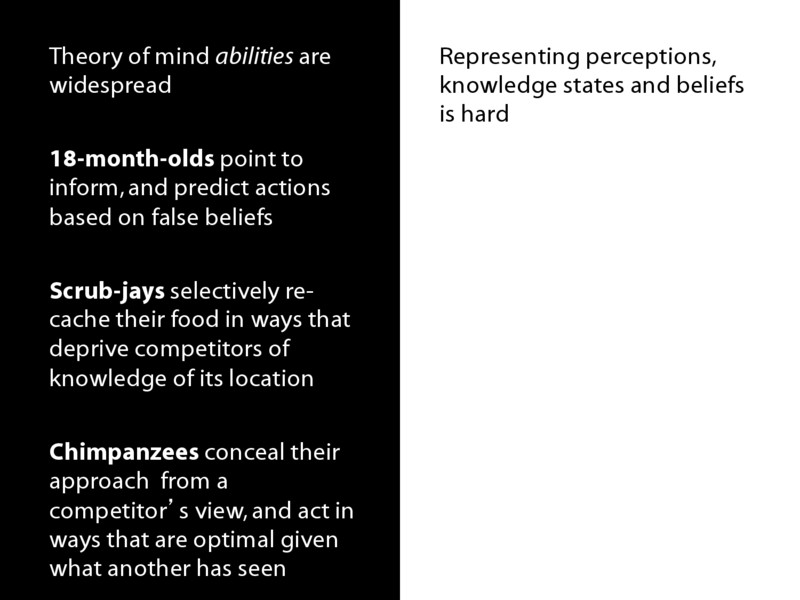

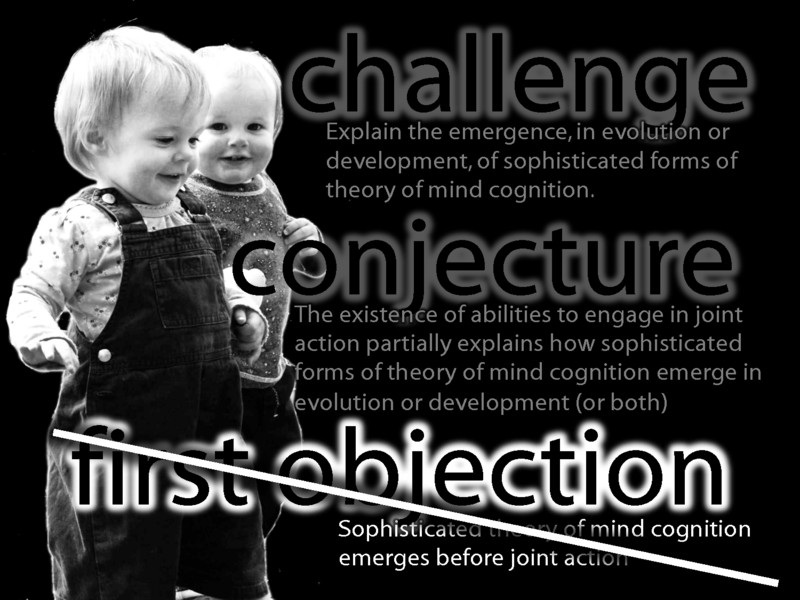

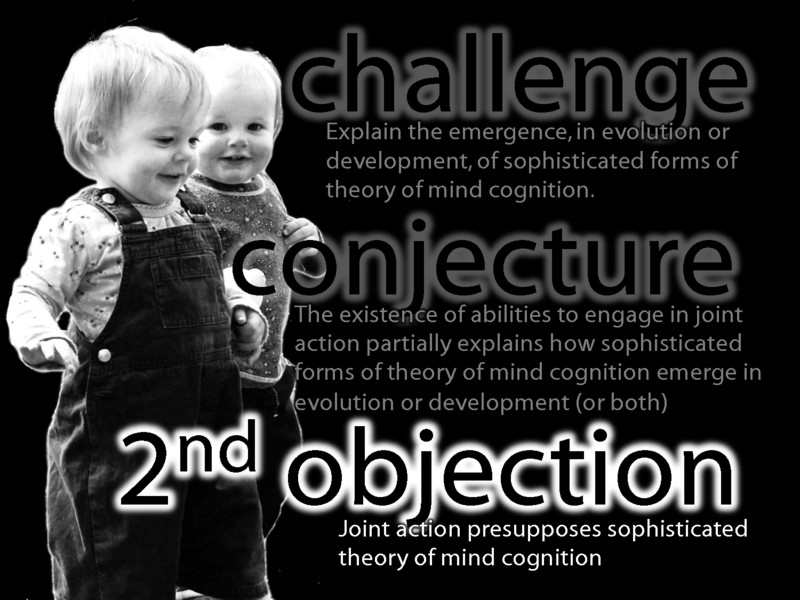

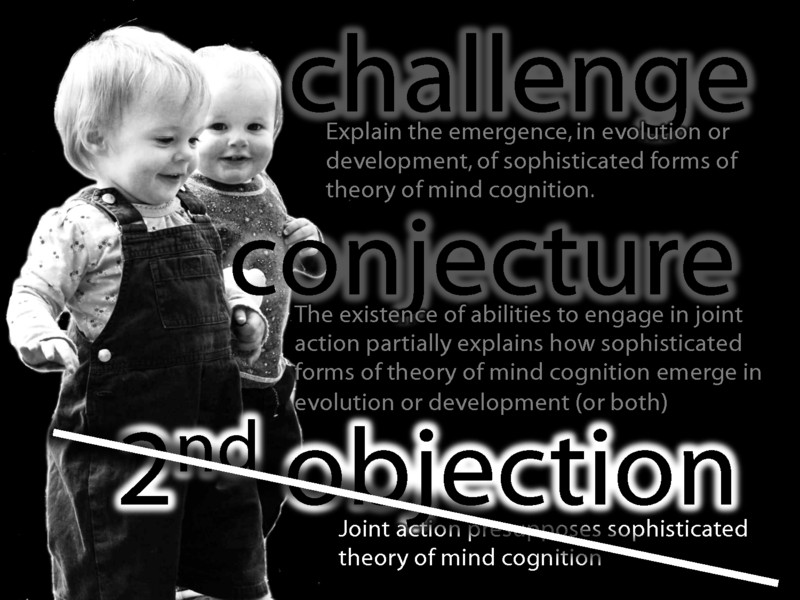

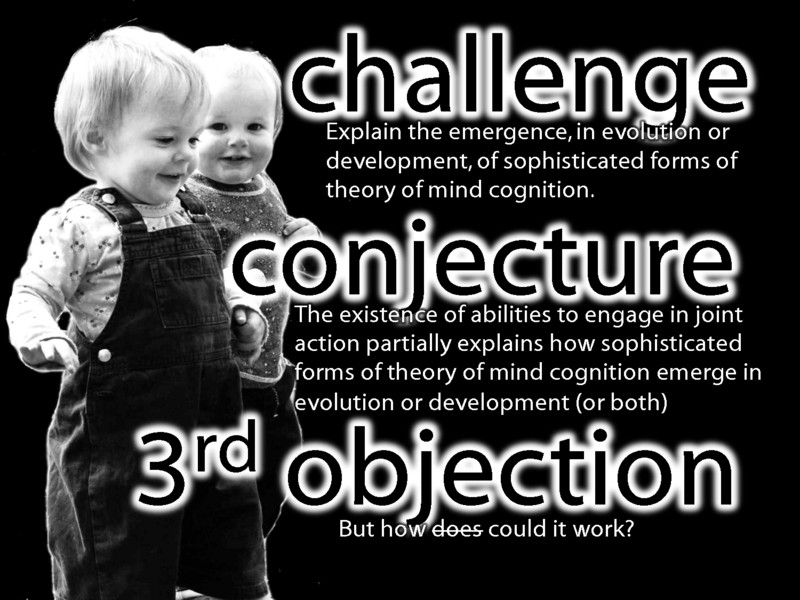

How can we explain the emergence, in evolution or development, of sophisticated forms of theory of mind cognition? One conjecture is that their emergence somehow involves joint action (Knoblich & Sebanz, 2006; Hughes & Leekam, 2004; Moll & Tomasello, 2007). This raises two questions. First, what forms of theory of mind cognition are required for joint action? Second, how might abilities to engage in joint action be involved in the emergence of full-blown theory of mind cognition? This talk will attempt to answer both questions.

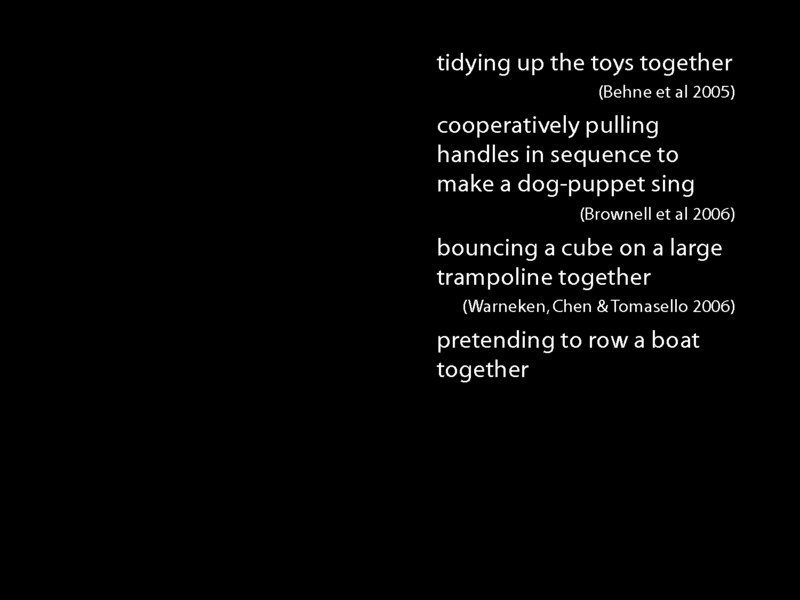

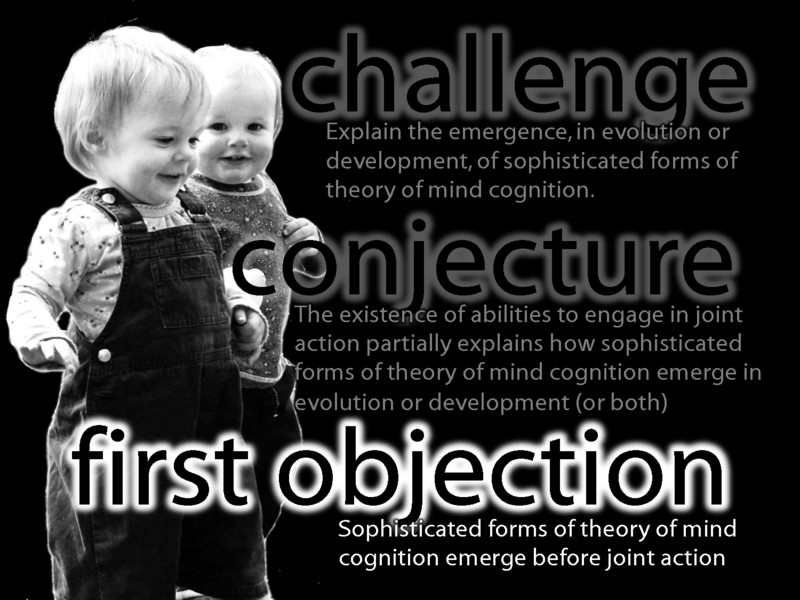

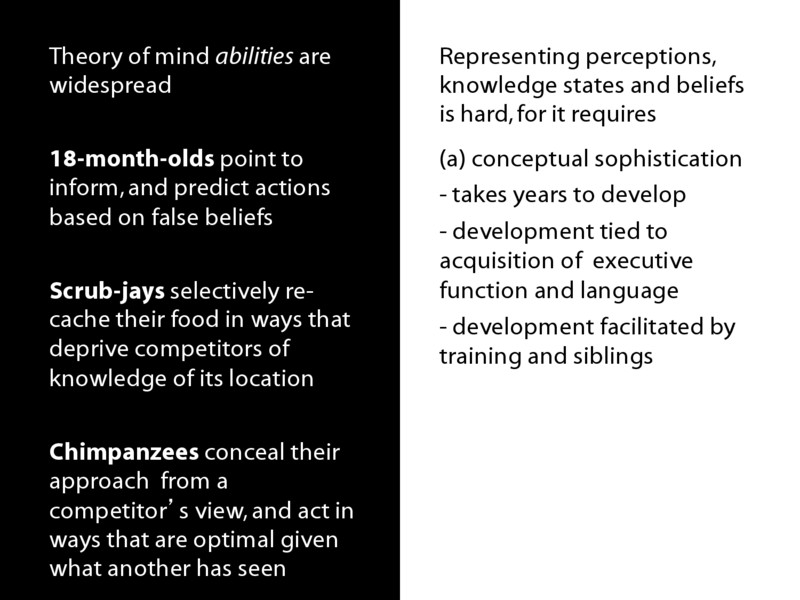

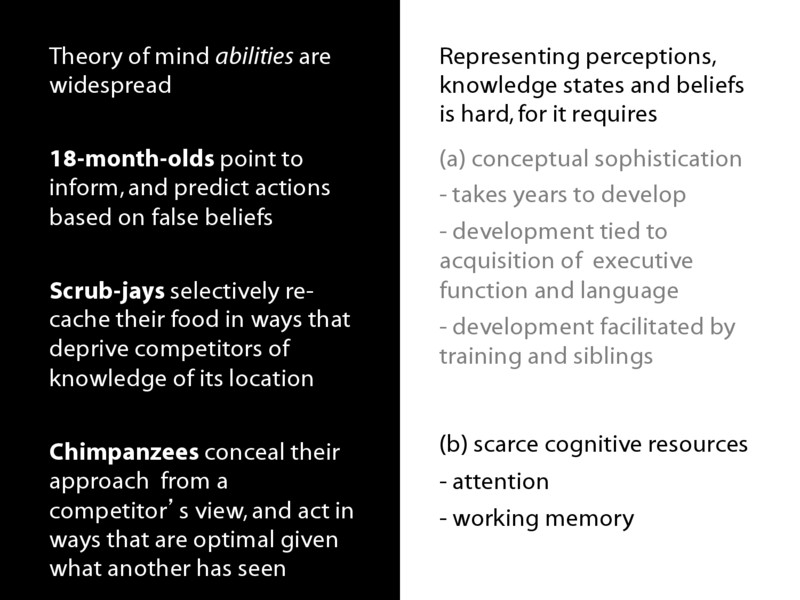

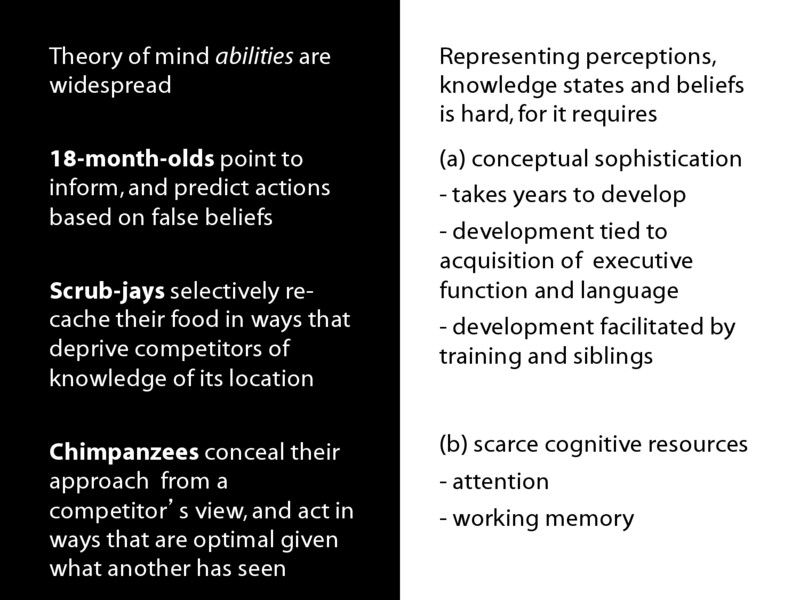

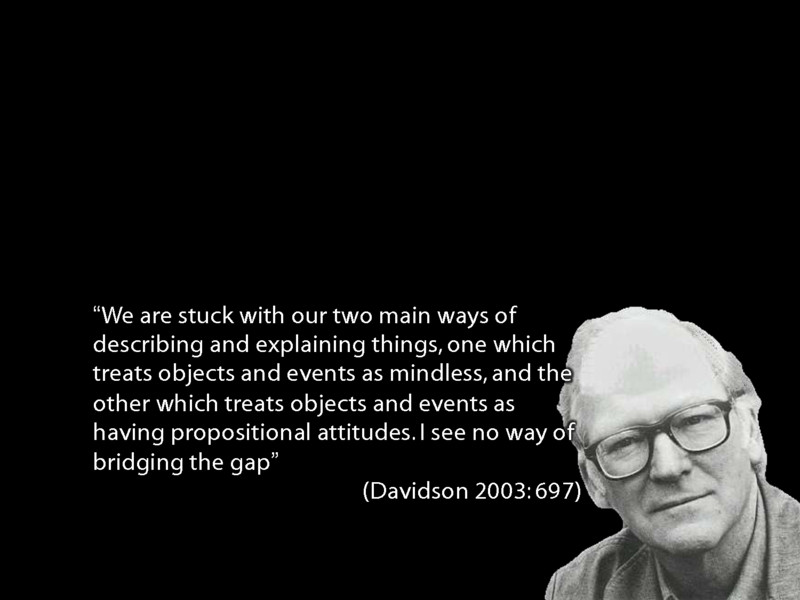

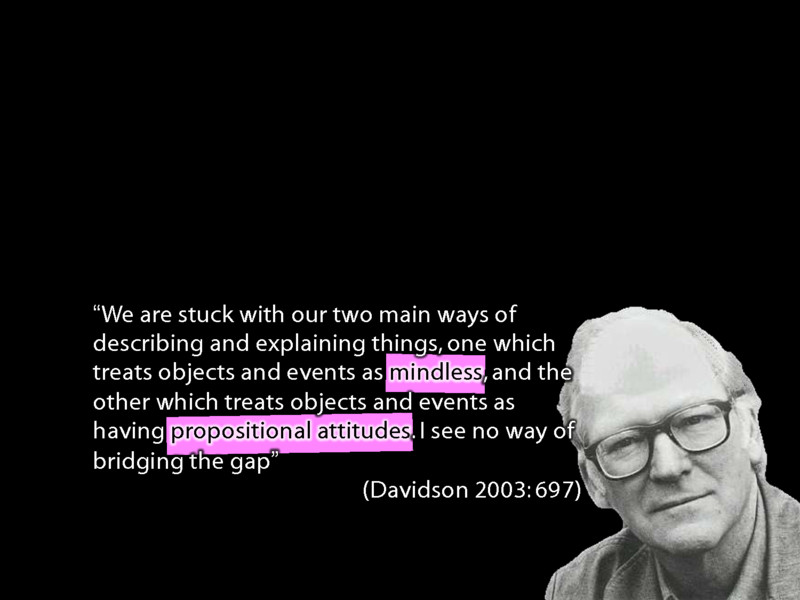

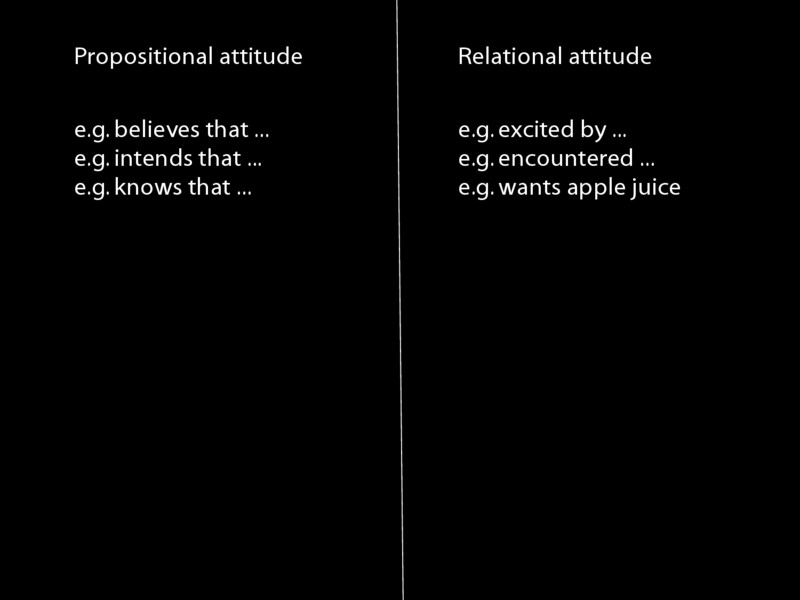

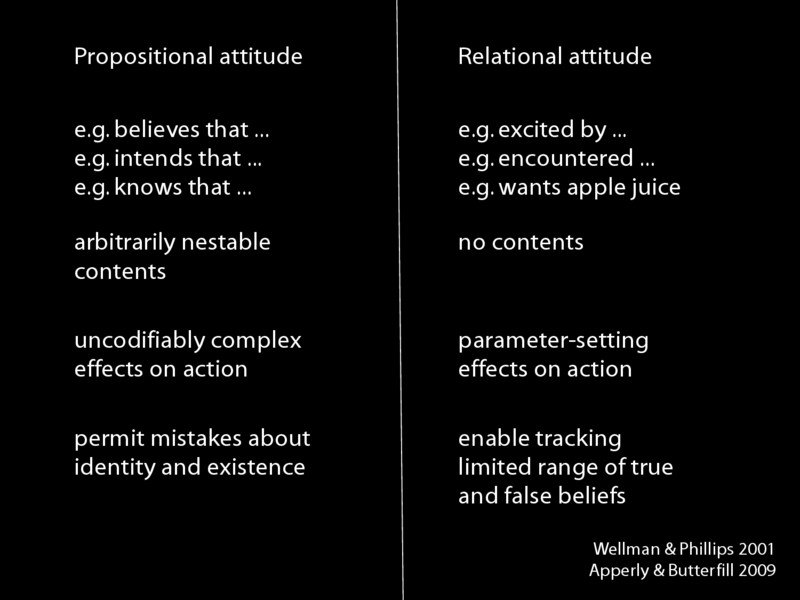

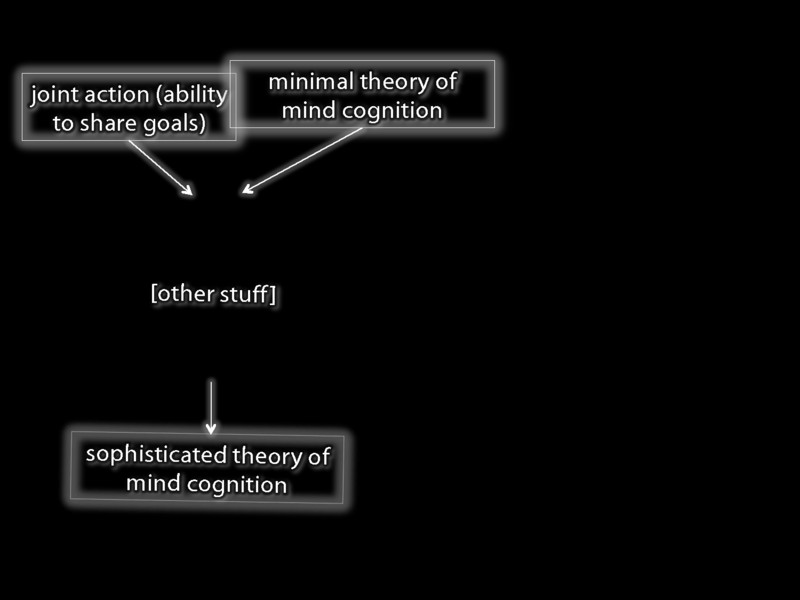

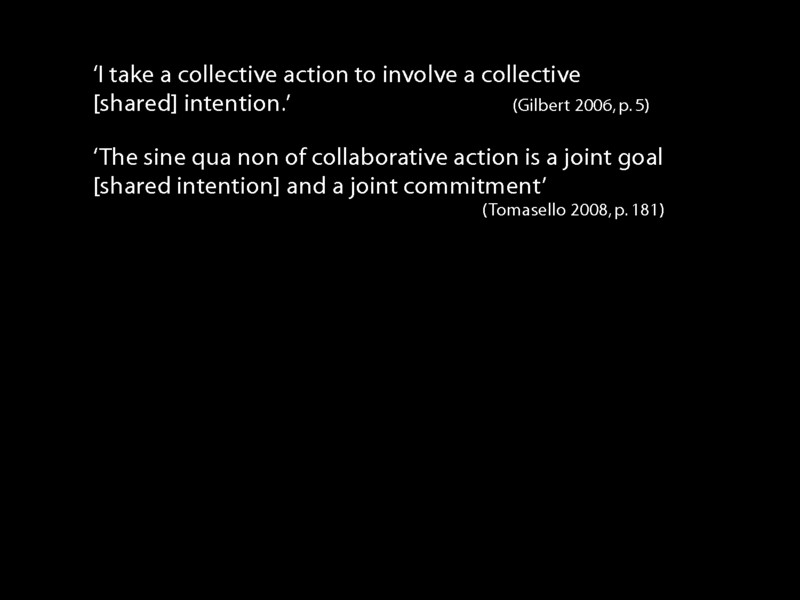

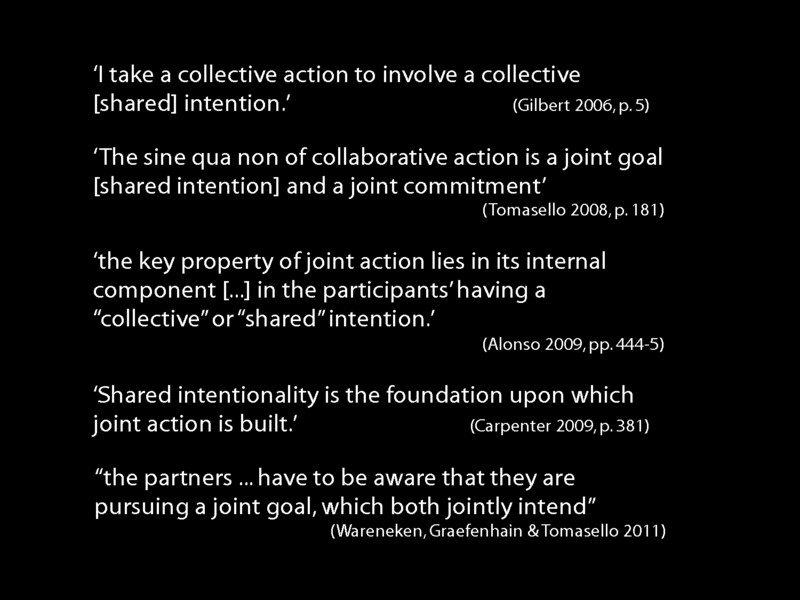

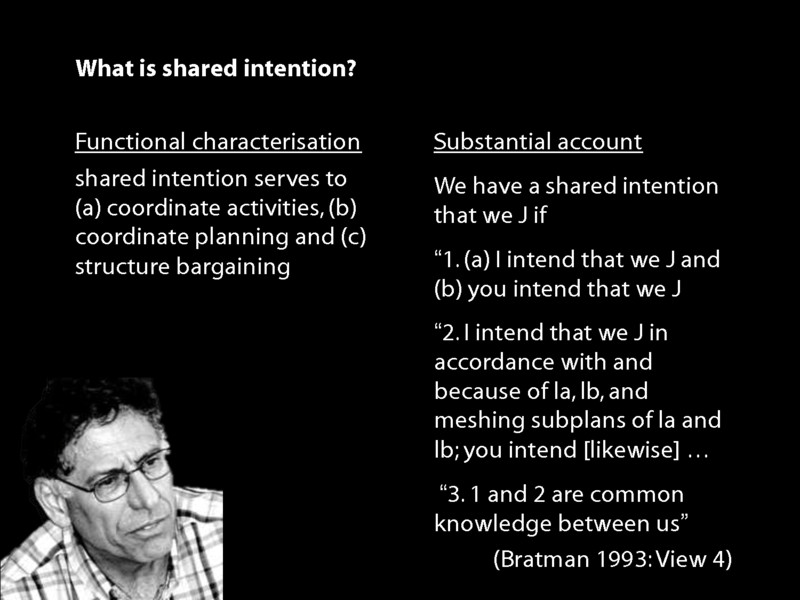

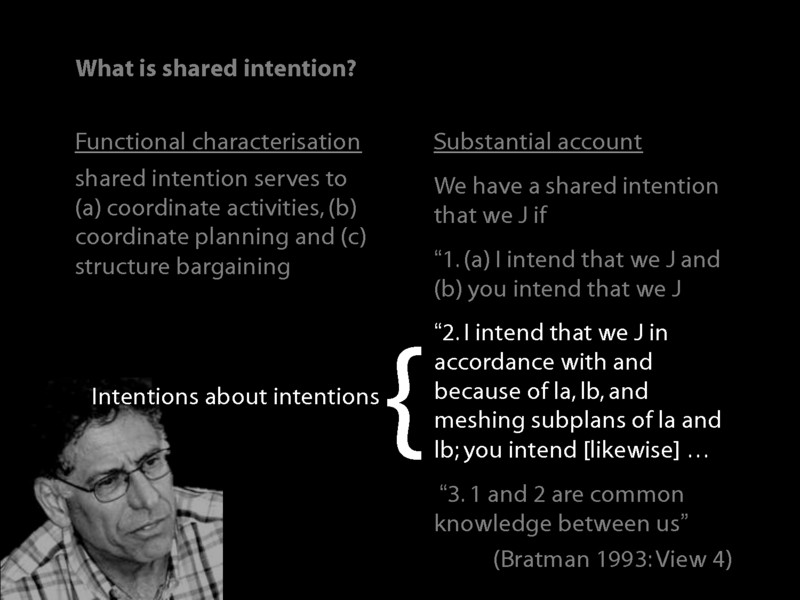

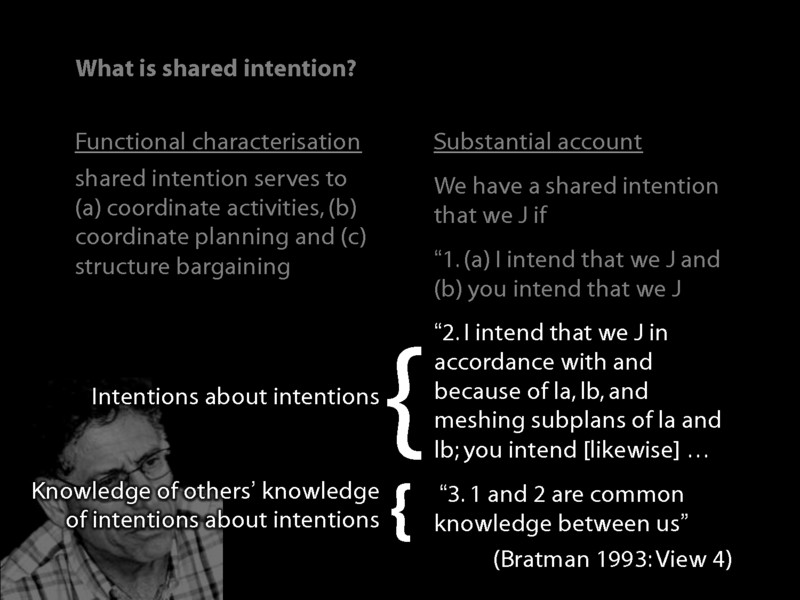

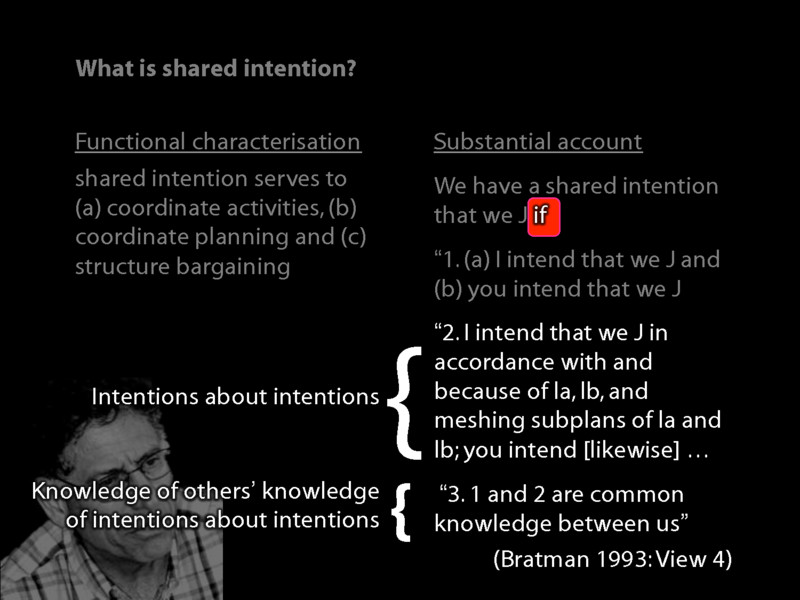

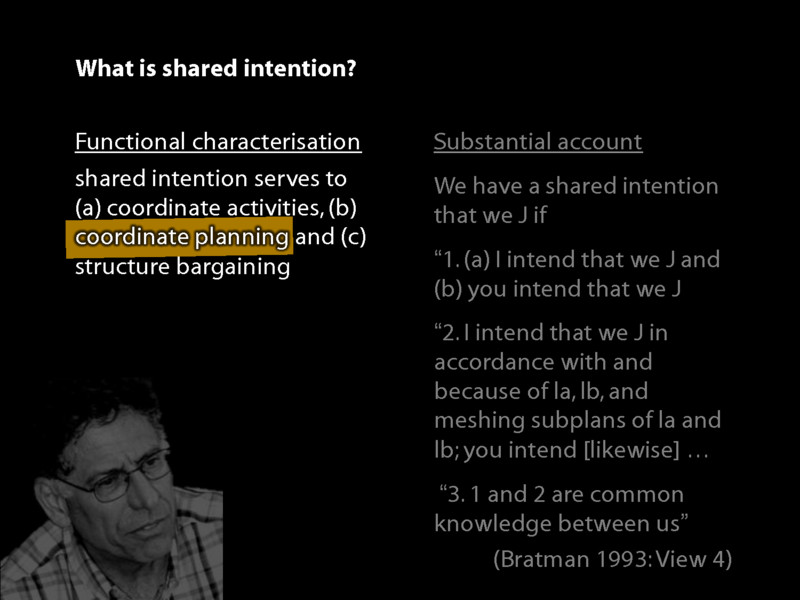

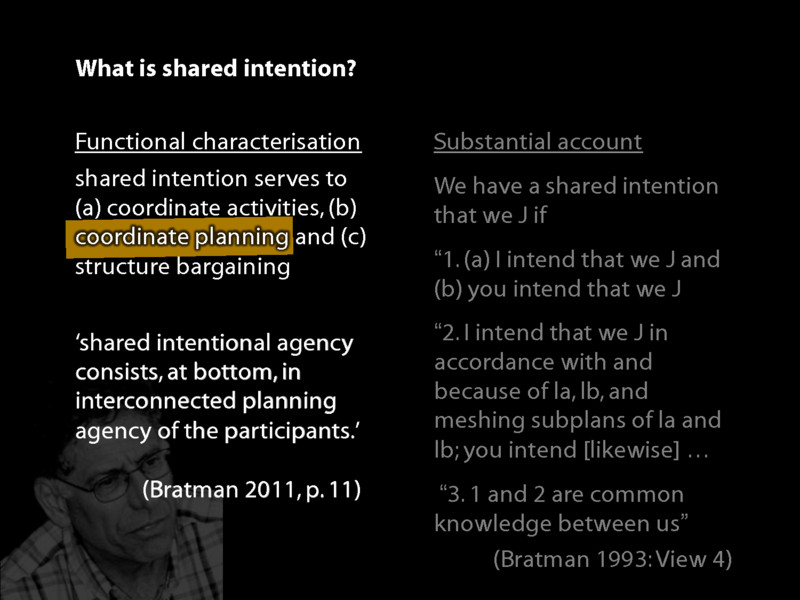

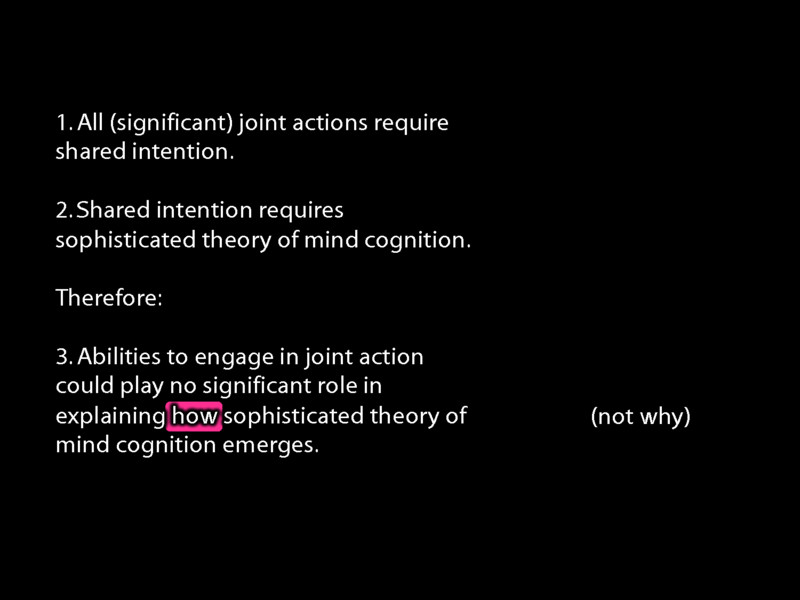

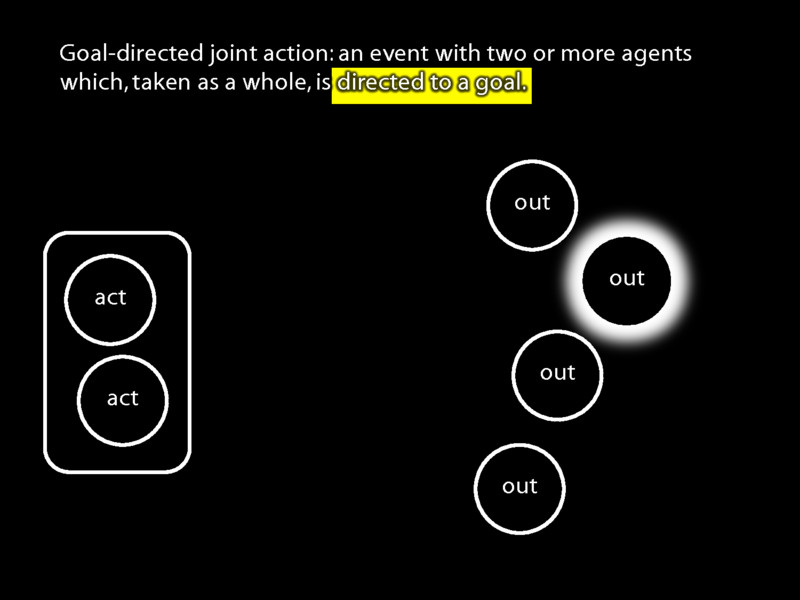

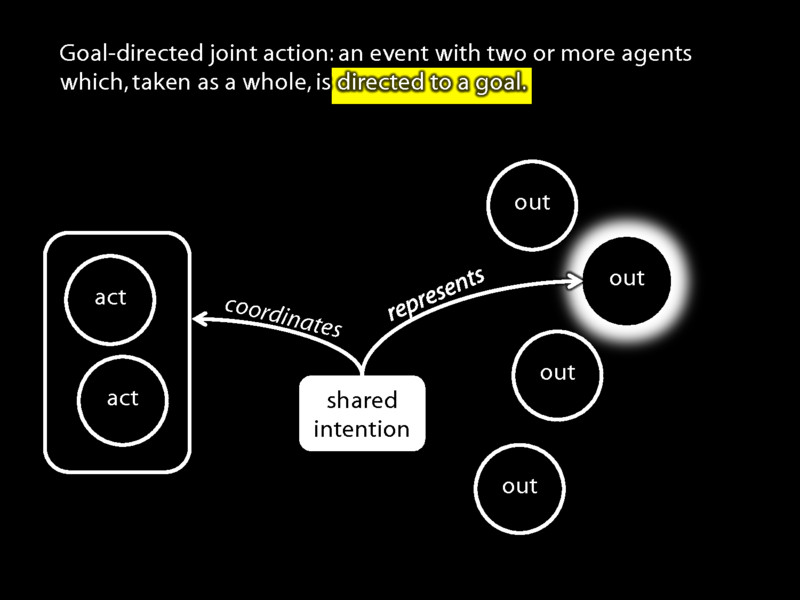

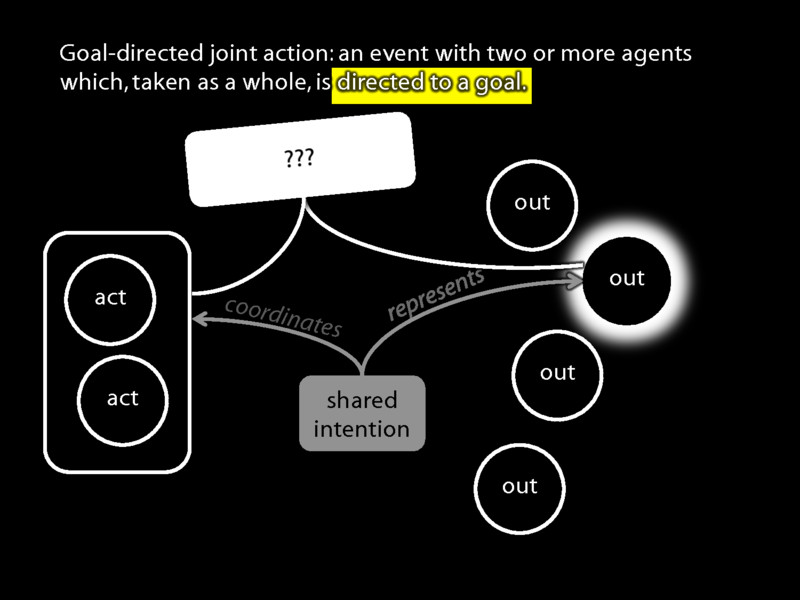

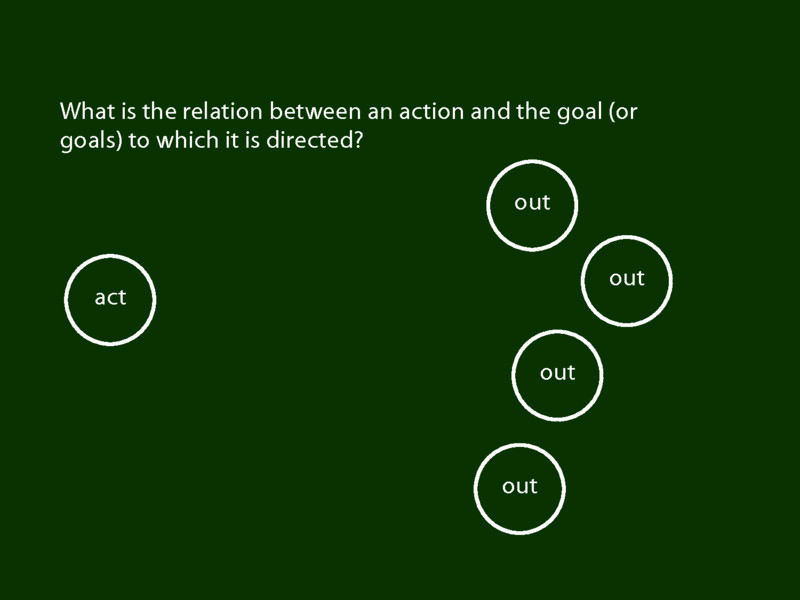

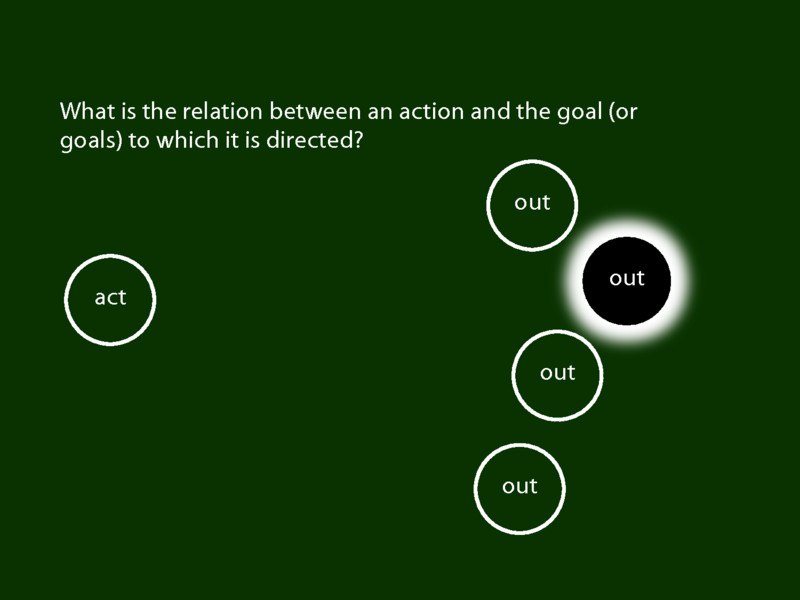

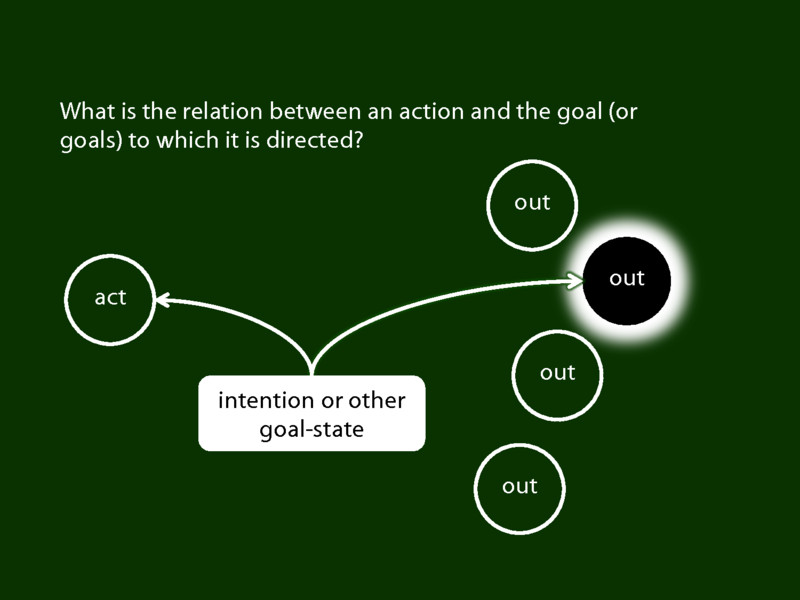

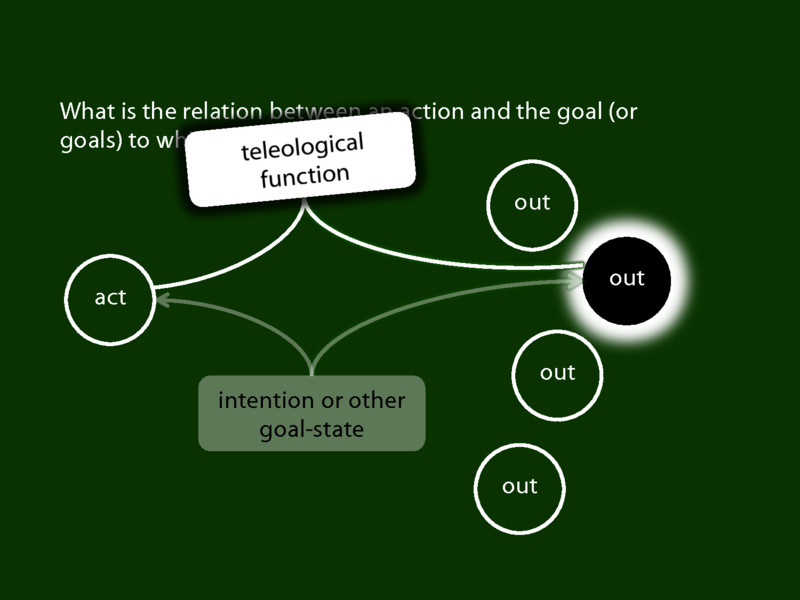

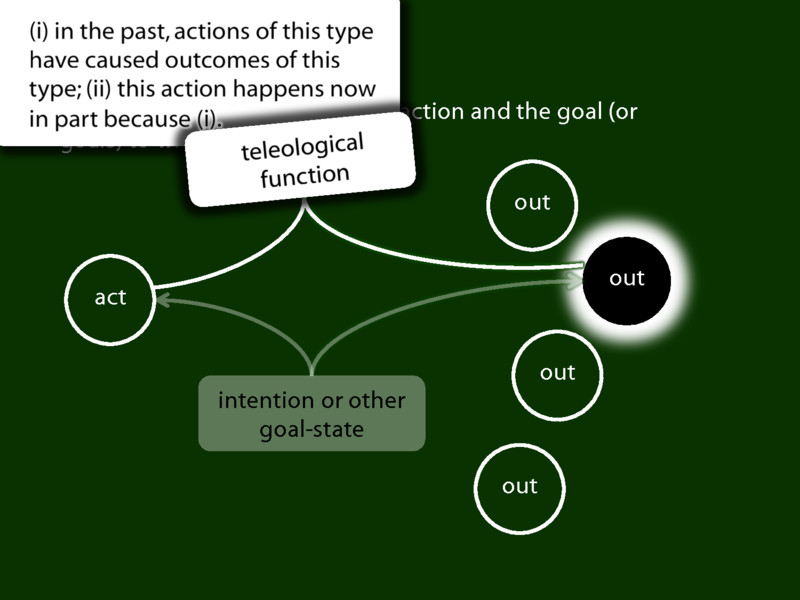

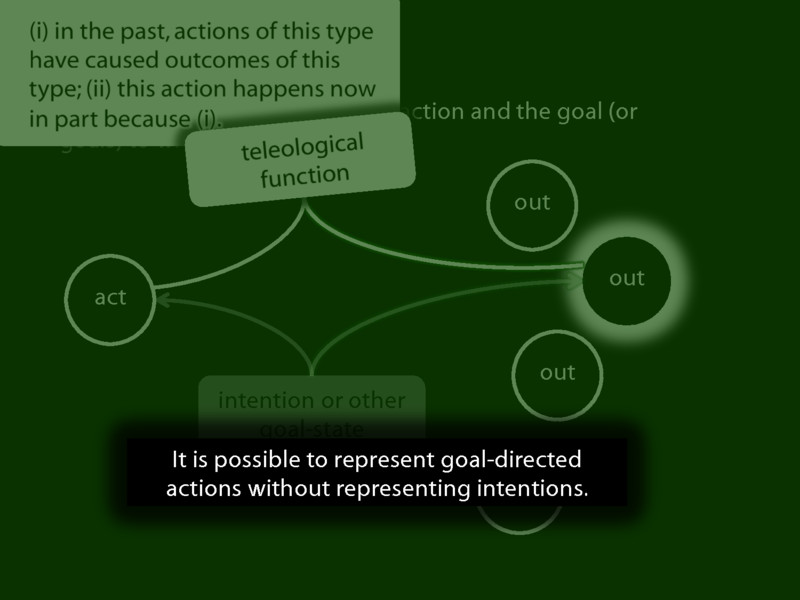

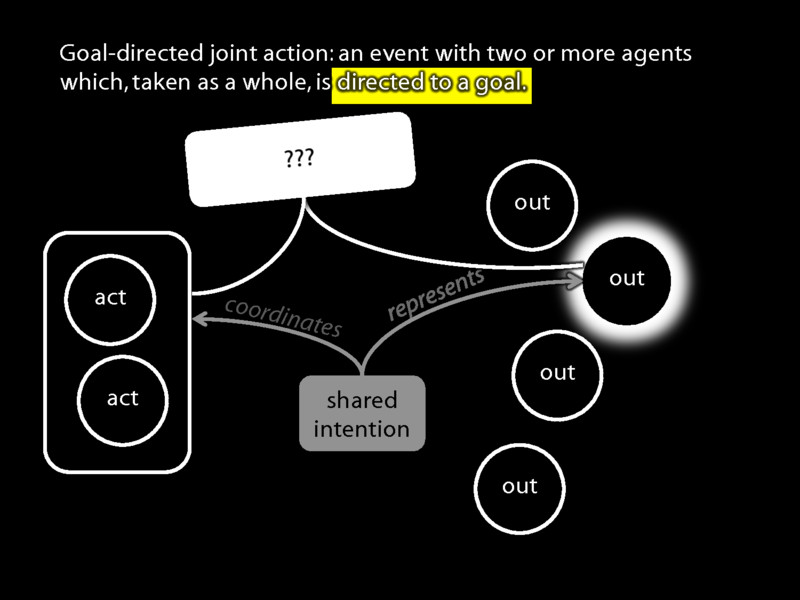

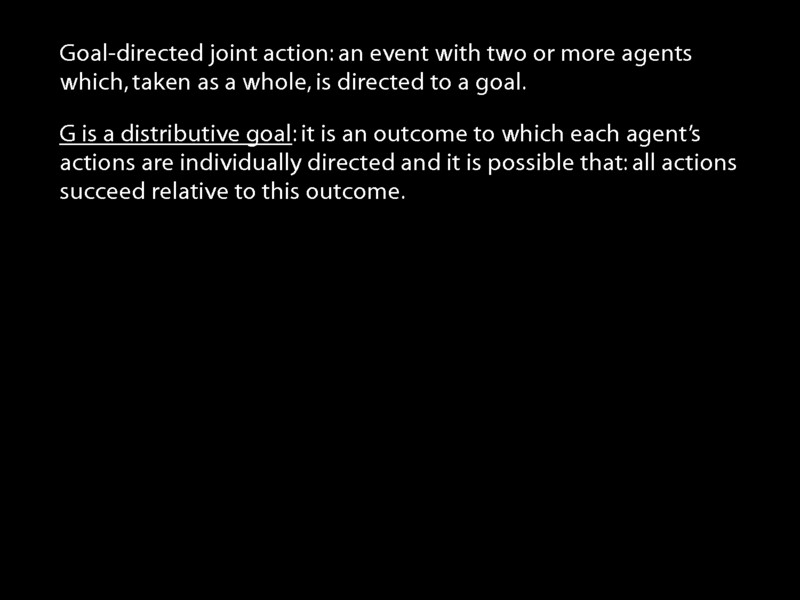

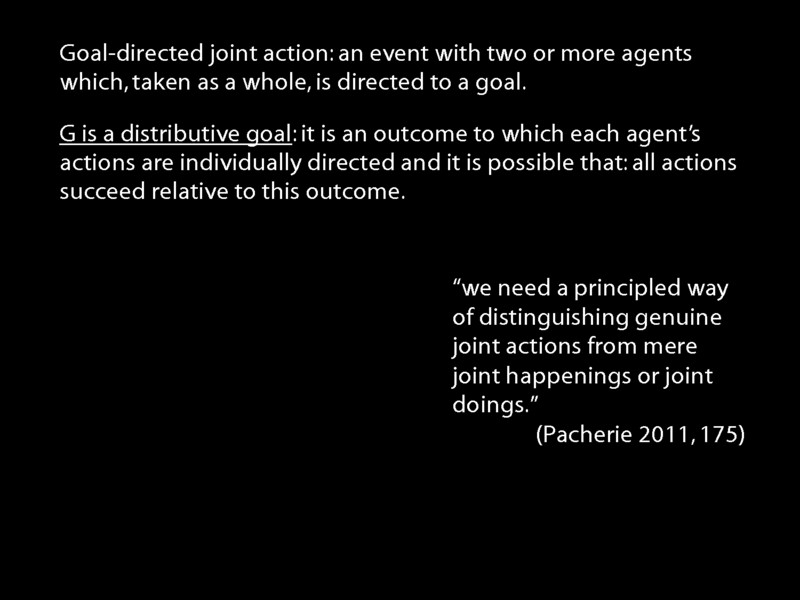

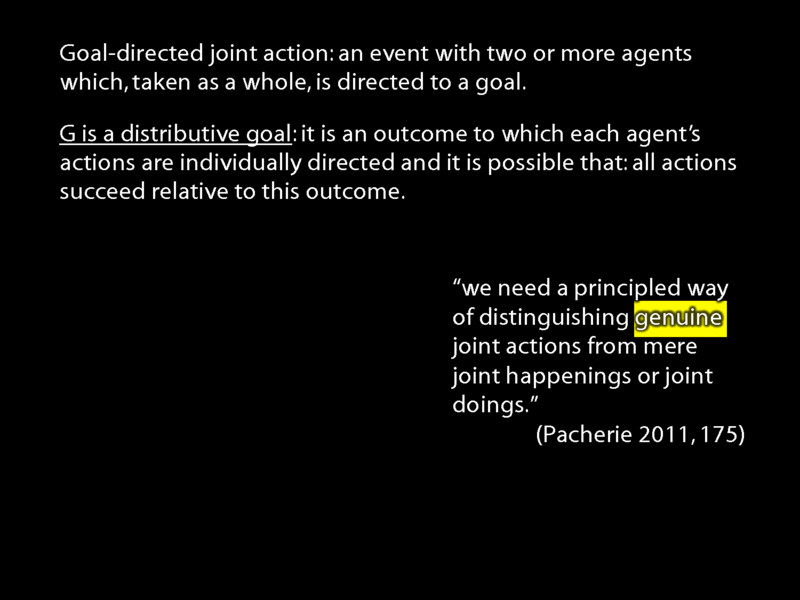

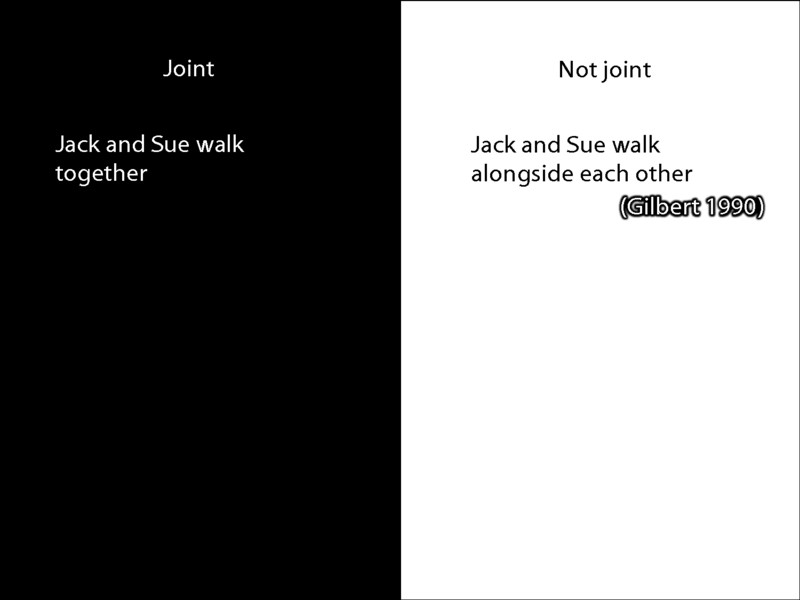

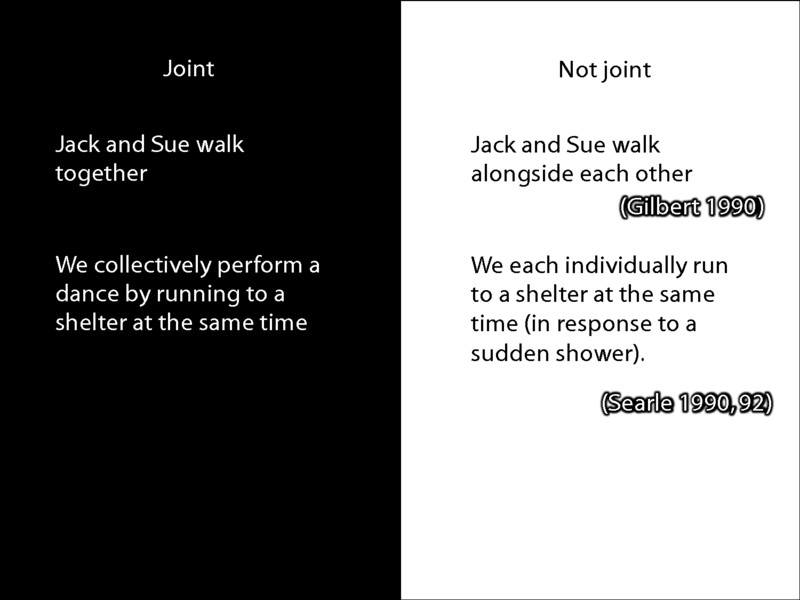

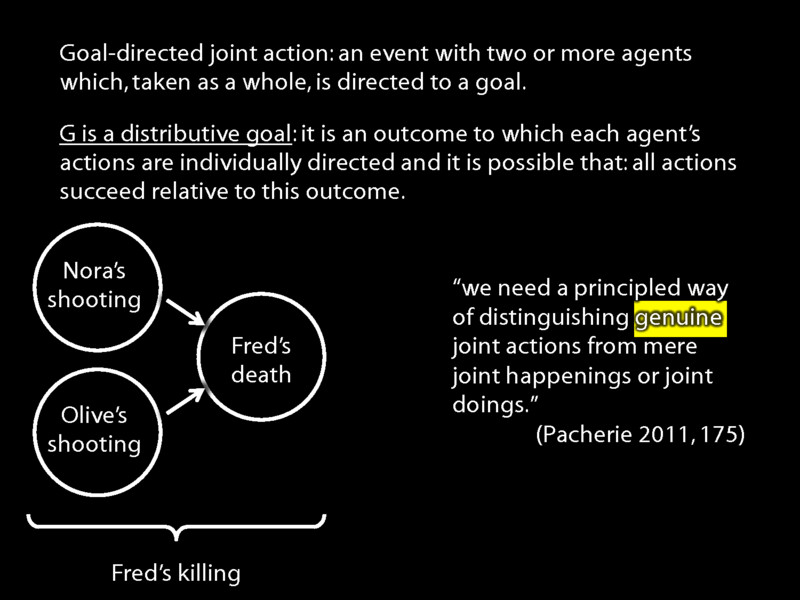

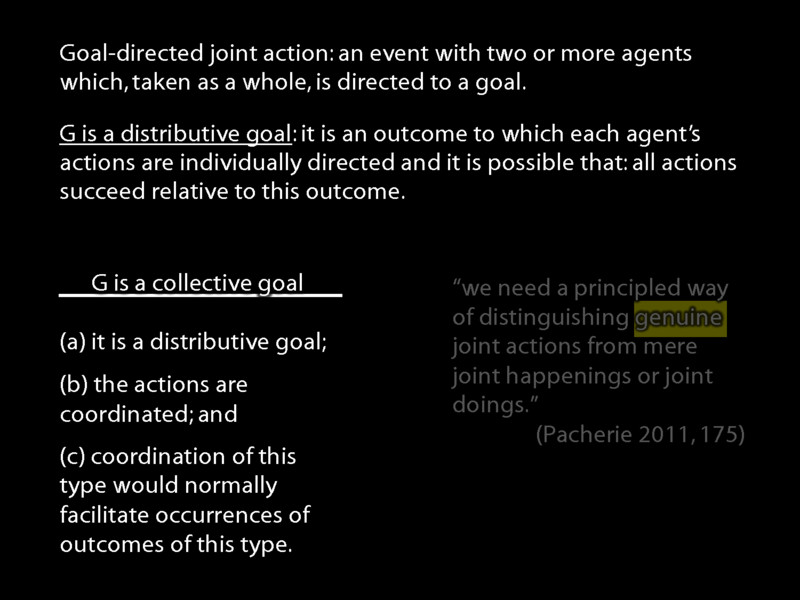

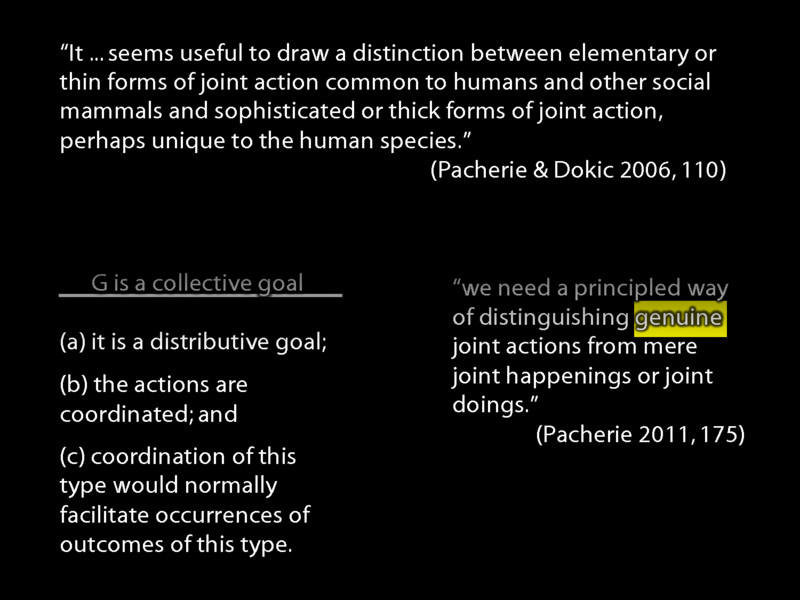

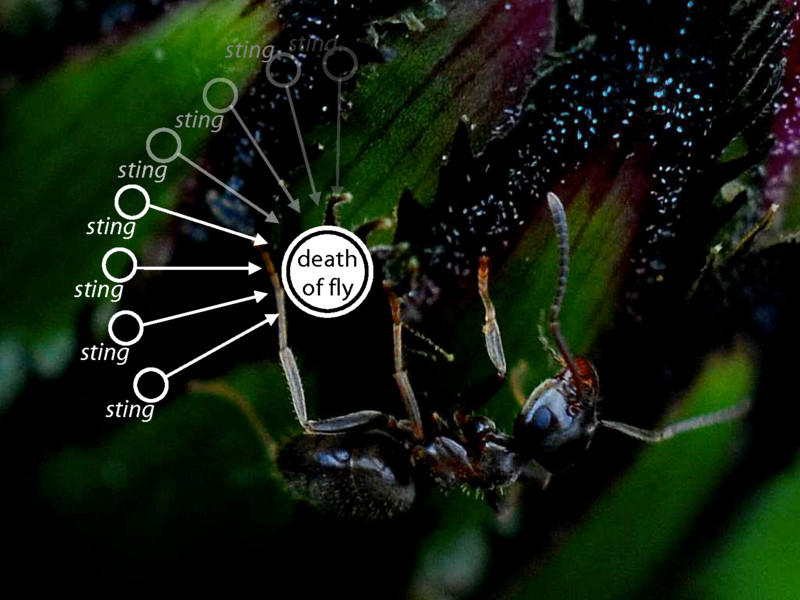

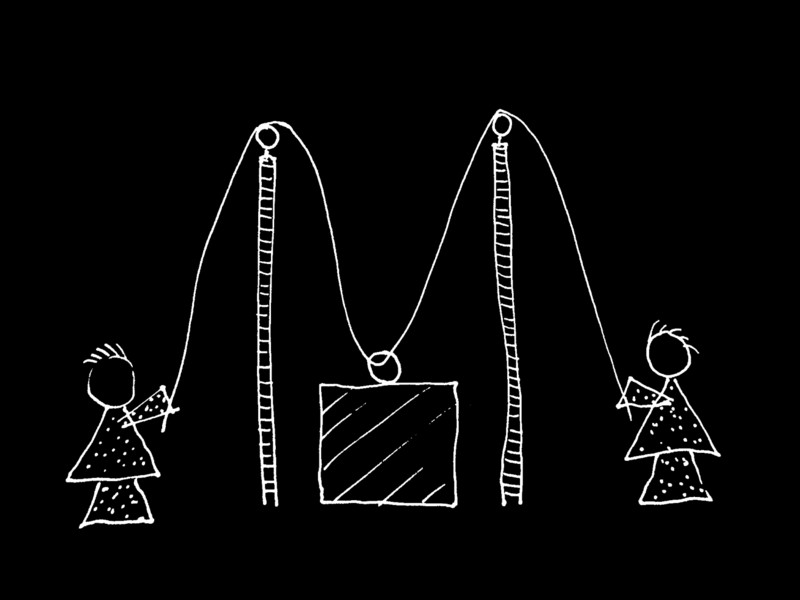

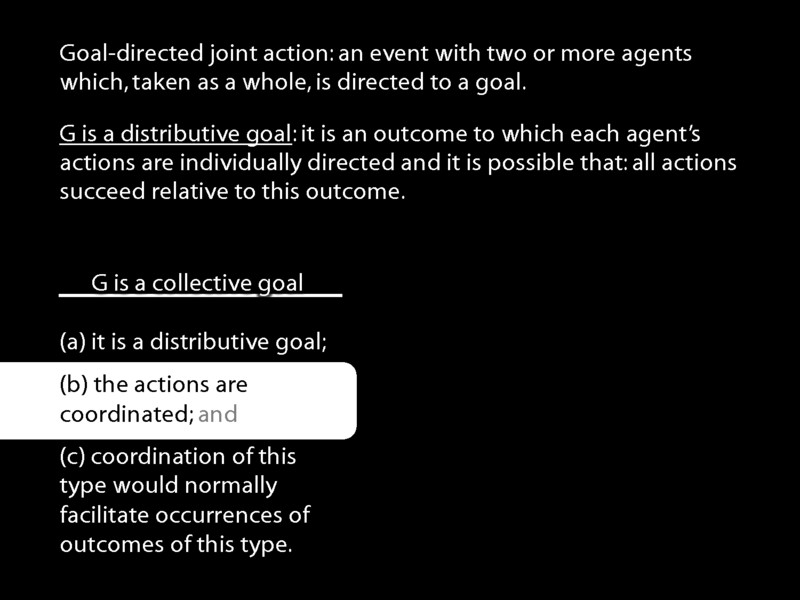

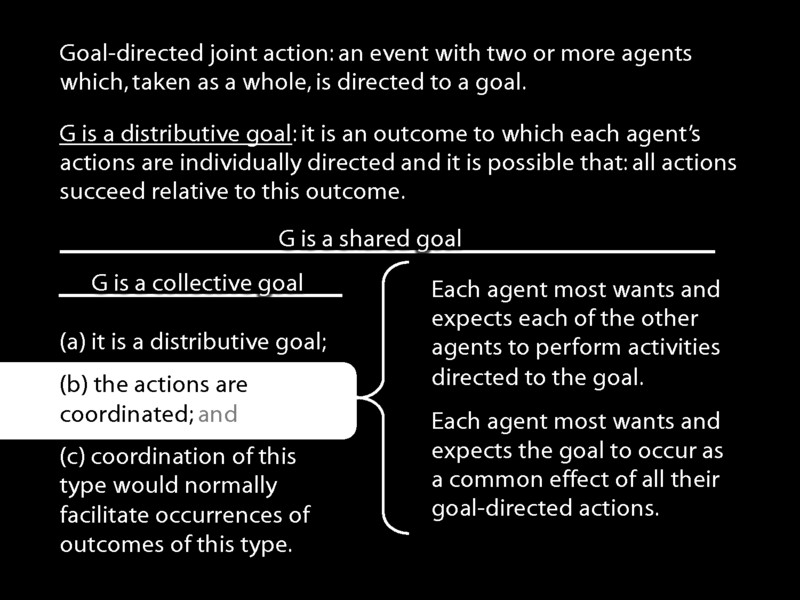

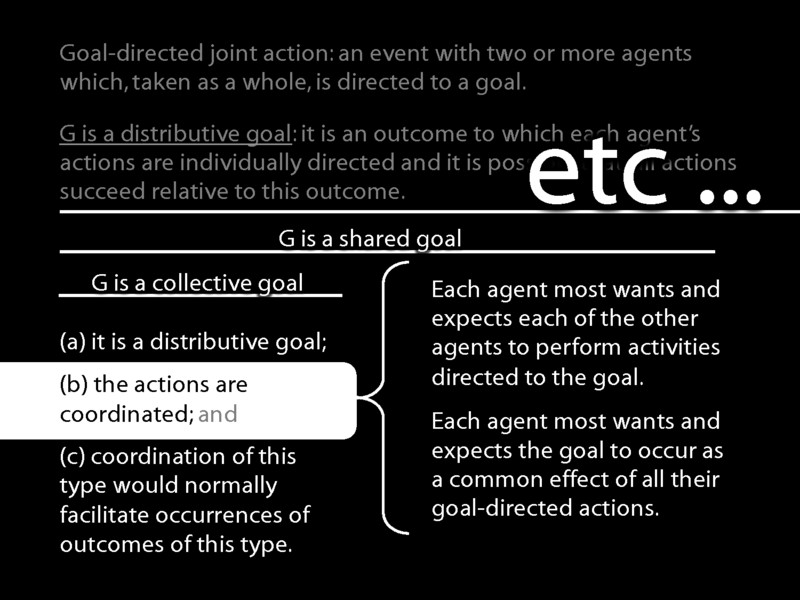

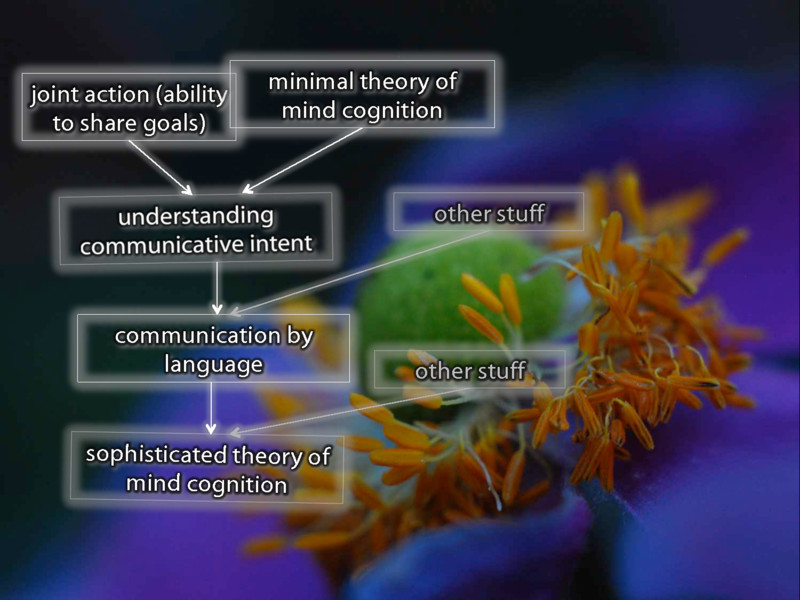

On the first question, it is often held that all joint action involves shared intention. This is problematic for the conjecture that abilities to engage in joint action partially explain the emergence of theory of mind cognition if, as I argue, shared intention presupposes theory of mind cognition at close to the limits of what humans are capable of. The problem can be avoided by rejecting the assumption that all joint action involves shared intention. I shall briefly defend an account of joint action without shared intention. On this account, joint action presupposes only minimal theory of mind cognition.

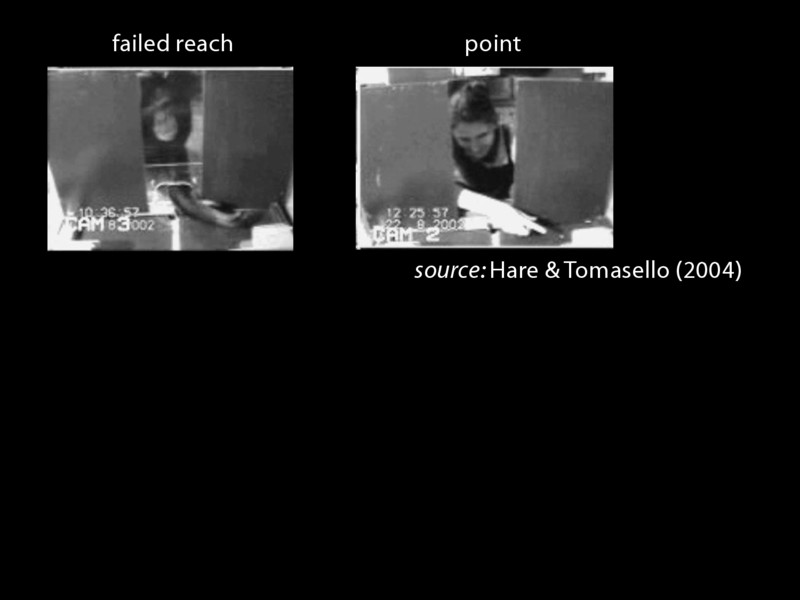

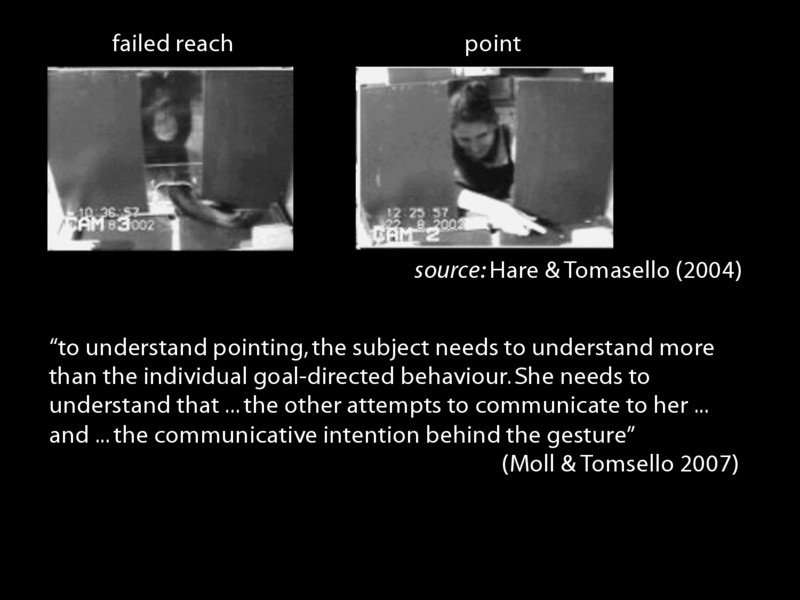

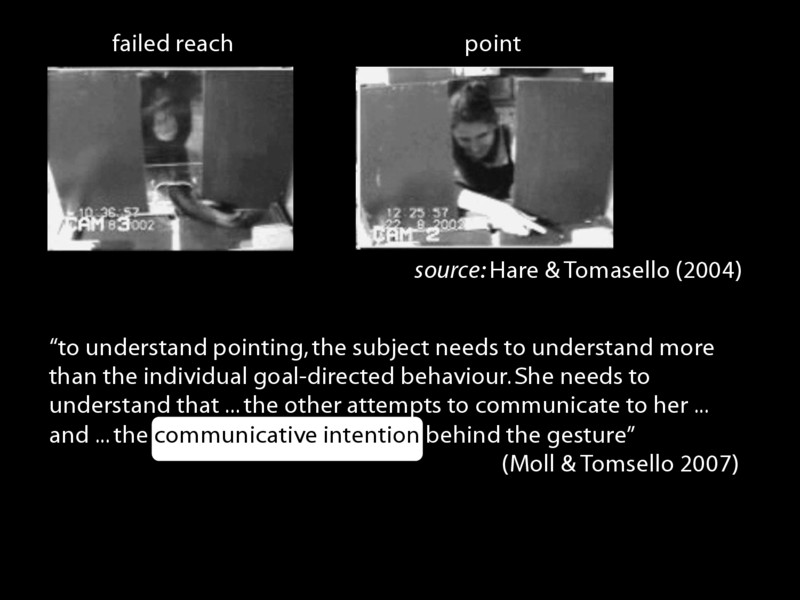

On the second question, I shall explain how abilities to engage in joint action provide a route to knowledge of others' goals distinct from ordinary third-person interpretation. This allows us to explain how humans are able to break into the Gricean circle and understand communicative intention. Because communicative intention is a foundation of communication by language, and because communication by language in turn plays a role in the emergence of full-blown theory of mind cognition (Astington & Baird, 2005), this may amount to one (indirect) way in which the combination of joint action with minimal theory of mind cognition partially explains the emergence of full-blown theory of mind cognition.